GHORBAN, DOB NON-EXISTENT

I first ran into Ghorban in Paris in 2010 when he was 12 years old, and was sleeping in the street. I saw a kid who was lost, who needed to be taken by the hand, but this little guy had just traveled 12,000 kilometers (7,500 miles) as an illegal migrant, starting in Afghanistan where he was born. I was flabbergasted. Alone he had coped with fear and faced the dangers of the migrant routes. I had been along such routes in Africa, the Middle East and the Mediterranean, and I knew just how tough they were. The survivors have endured ordeals which adults rarely encounter in the course of their lives.

In 2010, there were approximately 4000 unaccompanied children in France, and now it is estimated that there are five times as many. How do children who have lived through these adult experiences go on to build their own lives? How do they develop their own identity? How much of the past remains with them in their new cultural environment?

Ghorban was eager to tell his story, and we decided to tell it together. I had got to know him, and we trusted one another.

A few weeks after Ghorban reached Paris, an activist found him accommodation in an emergency shelter. This was the beginning of a long and difficult path for him to fit in and find his place in society. First he had to get official residency documents. An error in the translation of his documents had set his date of birth as November 31, a non-existent date, and this was to be a constant spanner in the works when dealing with administrative authorities over the years to come.

Ghorban’s father had died, and he had been taken from his mother to look after livestock. His one driving ambition was to go to school, but he was spending his days at the shelter doing nothing, and as time went by, Ghorban became cut off and withdrawn. Youth workers suggested he should see a psychologist who was working with Médecins sans frontières. I was allowed to cover most of these therapy sessions, together with the documentary film-maker Claire Billet. The quotes presented as captions provide the storyline all the way through to the liberating outcome.

Ghorban has managed to come to terms with his past, with the experience of being torn away, torn apart, and abandoned, and he has finally discovered that his mother had not abandoned him, for in 2017, he set out to find his mother.

I was with Ghorban over a period of eight years, until he reached the age of adulthood.

With support from CNAP (French national center for the visual arts.)

Ghorban came to Villemin Park, the meeting point for illegal Afghan migrants in France.

Paris, January 2010.

“In Afghanistan, they called me corolai, which means ‘orphan’ but as an insult.”

Villemin, Paris, January 2010.

“My parents divorced, and my father went to Iran and was killed. My mother married again, and abandoned me.”

By a bridge on the Canal Saint-Martin, Paris, January 2010.

“I knew there was a human smuggler, and I called him: “Sir, I’m poor, and I want to leave. Please do something to get me to Turkey.”

In Turkey we went from Van to Istanbul in a truck, without anything to eat or drink.”

Paris, January 2010.

"In Istanbul, I talked to another smuggler about getting to Greece in an inflatable dinghy. It was very dangerous.

I spent a month in Athens, getting nowhere. There were times when I thought I was going crazy.”

Canal Saint-Martin, Paris, January 2010.

“I asked God why I was all alone. Then God helped me. I managed to get onto a truck going to Italy.

Then one day, at Rome railway station, I hid under a bunk in a sleeper compartment, and I made it to Paris. With God’s help, I came to France.”

Juveniles being separated and taken to accommodation, square Villemin, Paris, January 2010.

“I want to grow up to be a good person, and study as much as possible.”

Emergency shelter, Kremlin-Bicêtre (Greater Paris), March 2010.

“I haven’t found the path to follow in my life.”

Emergency shelter, Kremlin-Bicêtre (Greater Paris), June 2010.

“In Afghanistan, when I said I wanted to go to school, the answer was always:

"Who’ll pay for your books? Who’ll work for us? Who’ll take the animals out to graze?’”

Emergency shelter, Kremlin-Bicêtre (Greater Paris), February 2010.

“I kept my worries bundled up in my heart.”

Paris, January 2010.

“I hate Afghanistan. I never want to go back there.”

Kremlin-Bicêtre (Greater Paris), June 2010.

“I’d like to find a foster family, with a father and a mother who’ll tell me what to do.”

Leaving the emergency shelter. Kremlin-Bicêtre (Greater Paris), June 2010.

“One day I was sent to a shelter, the next day to a hotel. I’ve been in France for a year now.

The youth workers say that’s nothing, but for migrants, every day counts.”

Leaving the Emergency shelter. Kremlin-Bicêtre, June 2010.

“Now that I’ve started school, I can’t think of anything else. I’m well behaved, I always do my homework, and all the rest.”

Paris, June 2014.

“I never told anyone at school that I was living in a hostel, that I wasn’t with my parents, or that I was undocumented.”

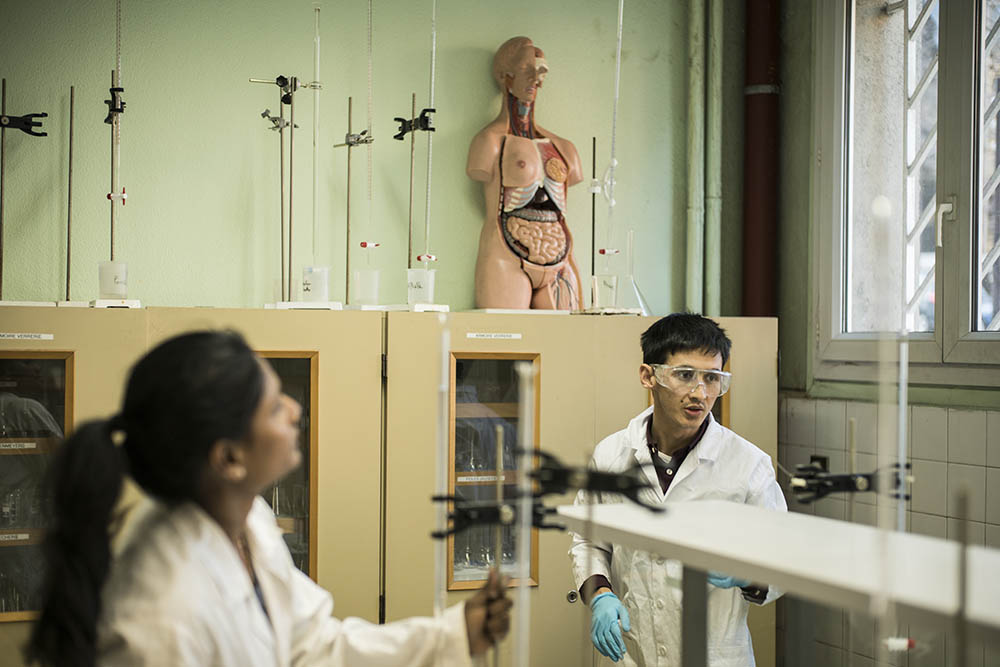

Vauquelin Vocational High School, Paris, December 2016.

“You’d think that I’d forgotten my mother. I don’t think about her very often, only when I’m in trouble at the hostel or at school.”

Ghorban’s room at his residential hostel.

Paris, January 2016.

“My mother had no other choice. She had to abandon me. One day I’ll go back and find her.”

Paris, September 2016.

Vauquelin High School.

Paris, December 2016.

“When I think about all the official documents I need to stay in France, I wake up in the middle of the night, and can’t get back to sleep.”

Paris, March 2016.

“It’s easier to talk when there are just boys. You can insult one another, you can do anything.

We just talk and laugh. With girls it’s not so easy to spend time like that.”

Paris, January 2017.

Studying for the baccalaureat in the school library.

Vauquelin High School, Paris, December 2016.

“I left Afghanistan one winter’s day. I didn’t have a cent on me, and I didn’t say good-bye.”

Ghorban celebrating both his 19th birthday and his French citizenship.

Paris, December 2017.

Internship in a pathology laboratory.

Paris, February 2017.

“If Marine Le Pen is elected president, I’m worried that she might cancel my citizenship.”

Ghorban voting for the first time, at the French presidential election.

Paris, April 2017.

Once Ghorban had his baccalaureat and his resident’s permit, he went to Afghanistan to find his mother.

Roissy, July 2017.

Ghorban at the public showers when he stopped.

Bamiyan, Afghanistan, July 2017.

His half-brothers, Sorhab and Mehrab, met Ghorban and took him to their village.

Yakawlang, Afghanistan, July 2017.

“I left Afghanistan eleven years ago.” Ghorban reunited with his mother and two half-sisters.

Lal wa Sarjangal, Afghanistan, July 2017.

“I thought you’d drowned on the journey,” said Ghorban’s grandfather.

Lal wa Sarjangal, Afghanistan, July 2017.

“We are very proud of you,” said Ghorban’s mother and stepfather.

Lal wa Sarjangal, Afghanistan, July 2017.

“Compared to the children in my country, I have been very lucky.”

Lal wa Sarjangal, Afghanistan, July 2017.

“It is so good to know that I’m not alone, that I have a family.” Ghorban with his half-brothers and sisters.

Lal wa Sarjangal, Afghanistan, July 2017.

Ghorban with his half-brothers, Mehrab and Sorhab.

Lal wa Sarjangal, Afghanistan, July 2017.

“You shouldn’t make your children work.”

Ghorban’s half-sister Aziza and his half-brother Mehrab are working with their father, harvesting poppy seeds grown on their land.

Lal wa Sarjangal, Afghanistan, July 2017.

“I’m more used to living in France than Afghanistan.”

Lal wa Sarjangal, Afghanistan, July 2017.

“It’s not her fault or mine. It was just our fate.” The men in the family forced Ghorban’s mother to abandon her son.

Lal wa Sarjangal, Afghanistan, July 2017.

“What’s past is past, but you have to offer children a future.”

Ghorban wants his mother to move to the city so that his half-brothers and sisters can go to school.

Lal wa Sarjangal, Afghanistan, July 2017.

Ghorban has decided to stop studying and find a job in France so that he can help his family.

Lal wa Sarjangal, Afghanistan, July 2017.