TRAVEL JOURNAL OF A CLANDESTINE IMMIGRANT

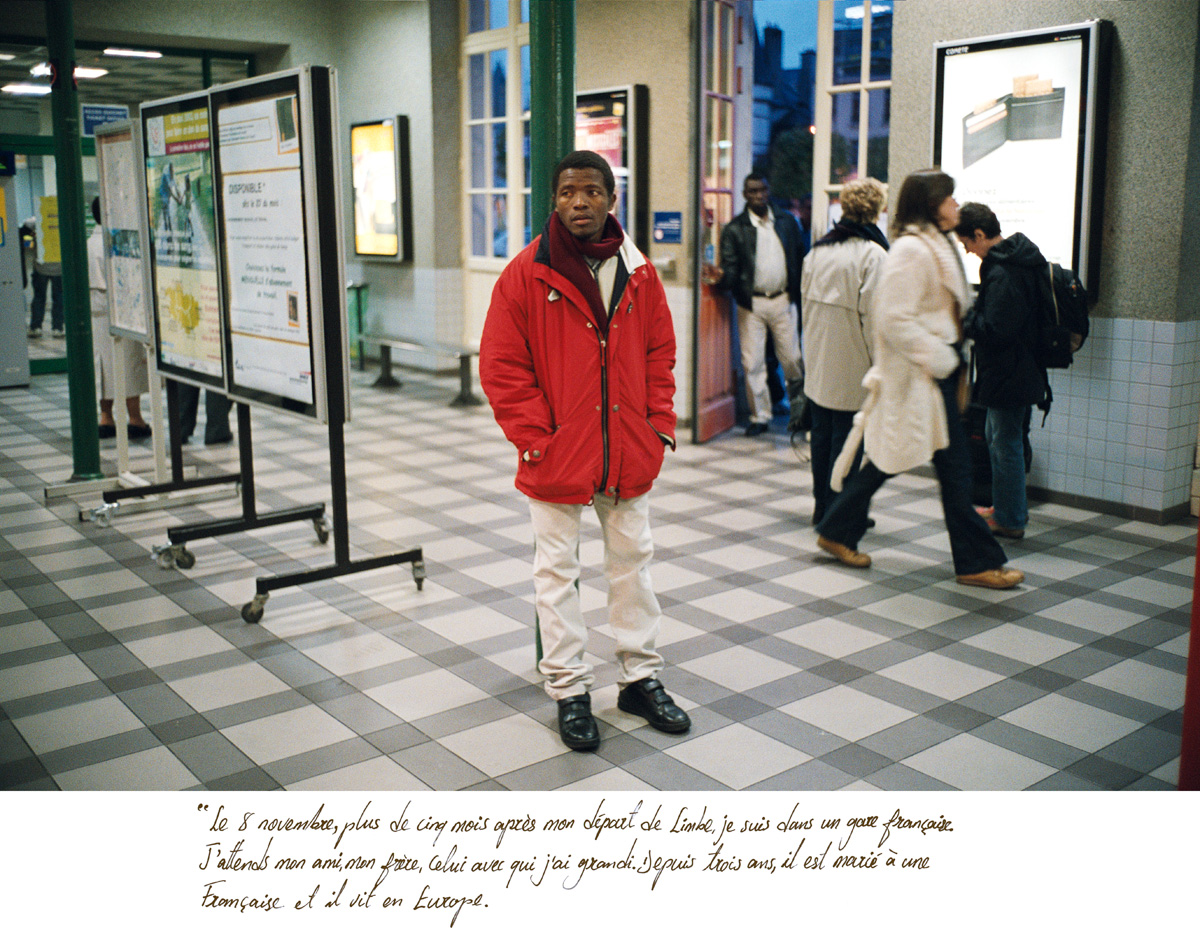

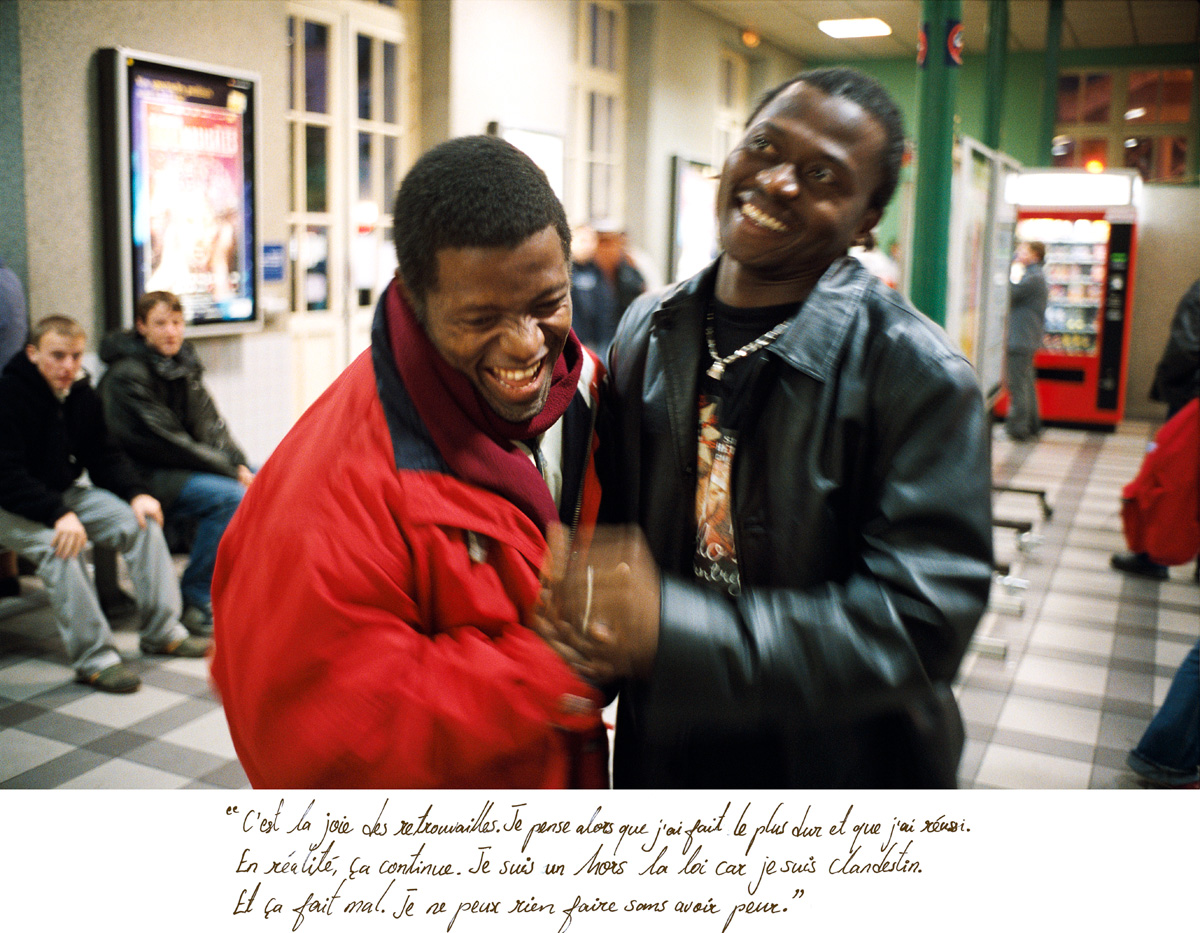

I crossed paths with Kingsley in Cameroon, somewhat by chance. While meeting friends, he confided in me his desire to leave. He had attempted the Journey two years earlier but had been forced to turn back due to lack of money. After that failed attempt, he took the time to save, with the support of relatives. He was now expected in France, since his best friend, Francis, had managed to immigrate legally after getting married.

Six months later, Kingsley told me he was preparing to leave again, and he agreed that we would travel together.

To ensure he kept control of his own story, I suggested that he write texts to accompany my photographs. He kept a travel journal throughout his entire journey.

I was aware of the chasm separating us — him, and me, the Frenchman, white, and holder of a passport. At first, our relationship was based on a shared interest: getting as far as possible. Then he asked me to be present when a relative handed him some money. I became a guarantee of seriousness. Later, he asked me to keep his savings so that he wouldn’t be robbed when crossing borders. I accepted, knowing that this gesture bound him to me in an irrevocable way.

A deeper relationship grew between us through the hardships we shared on the migration route. A solid trust took hold. What we went through together, and the mutual respect we feel, binds us to each other unshakably.

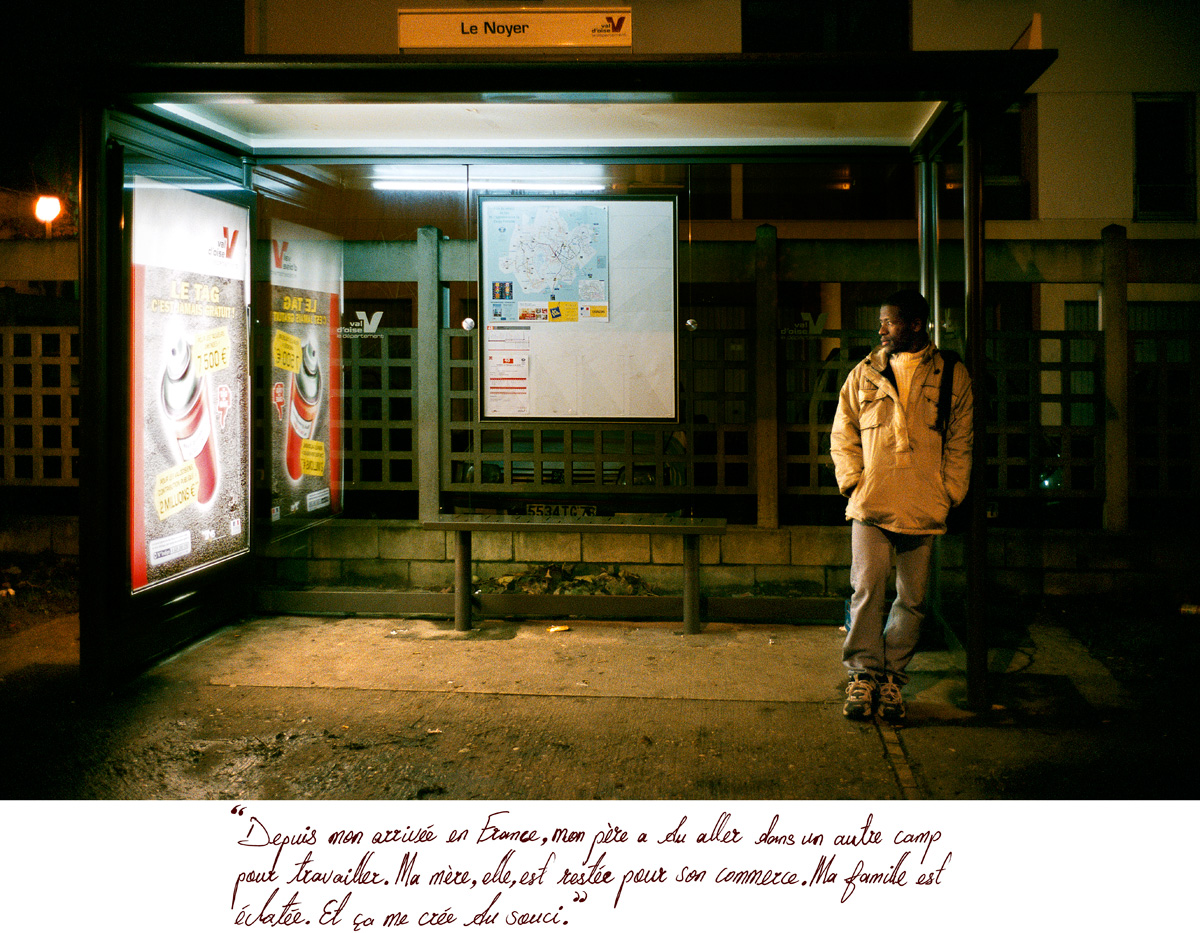

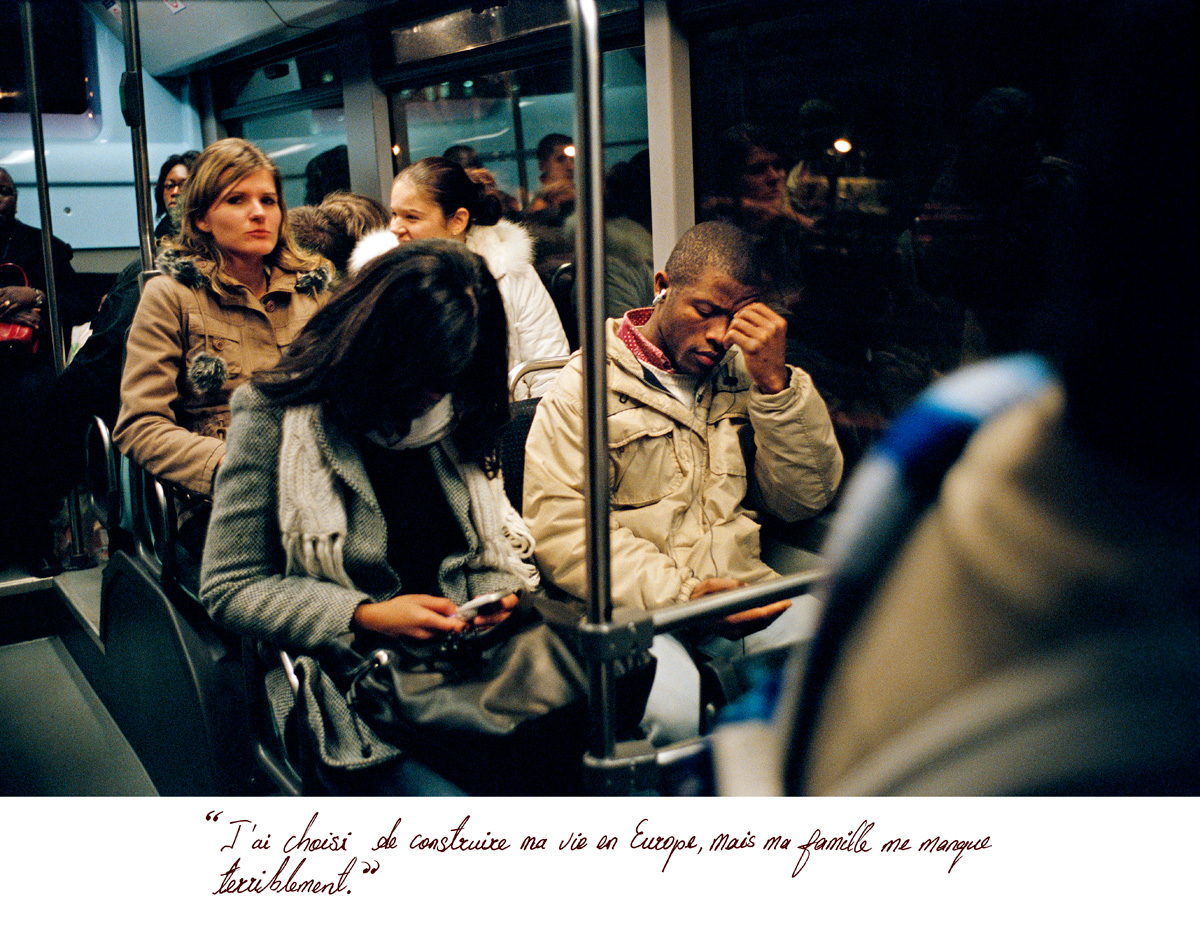

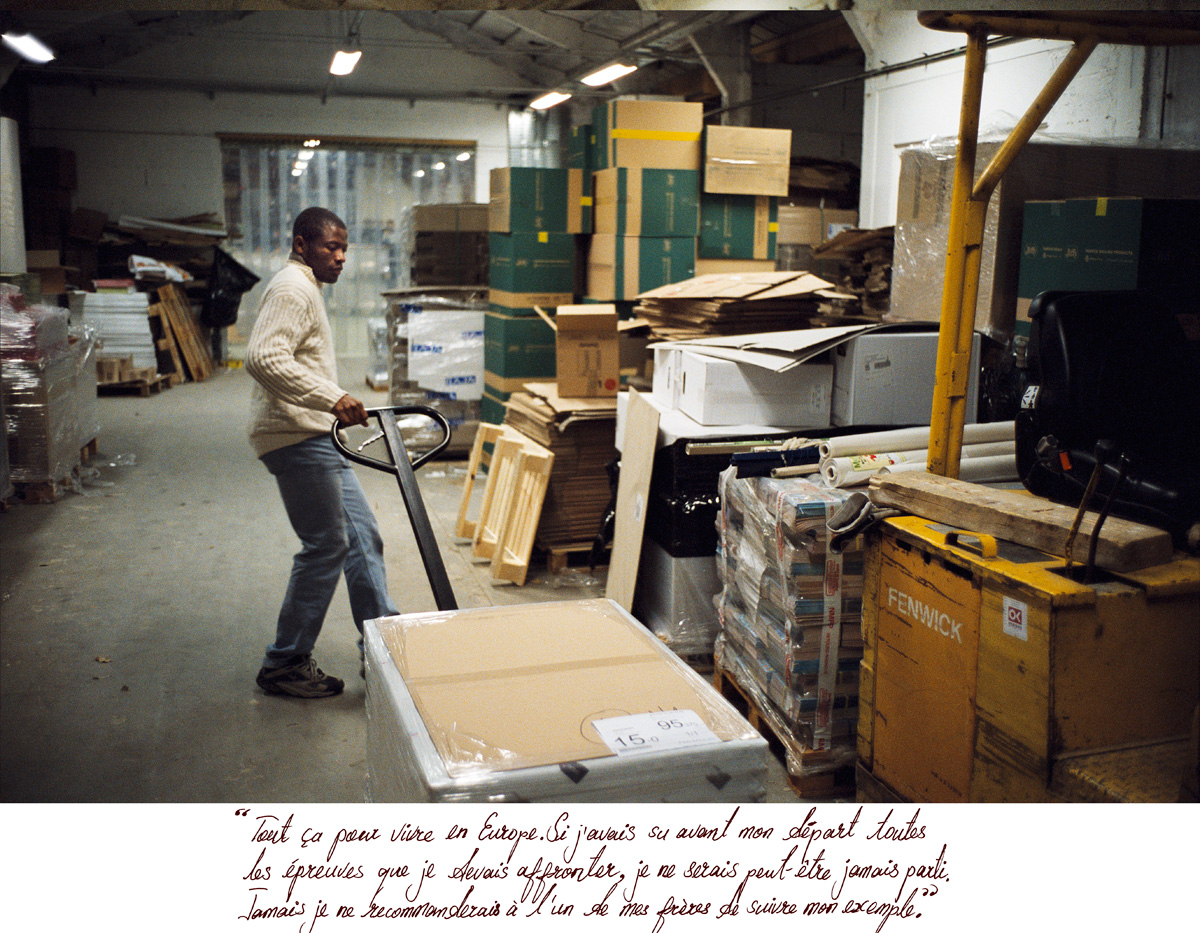

Kingsley arrived in France in 2004. Today he lives in Seine-et-Marne, owns a house, and works — on a permanent contract — for an air-conditioning maintenance company. He was the witness at my wedding. Kingsley and his wife are now the parents of a little girl: Ruth was born in May 2025.

April – November 2004

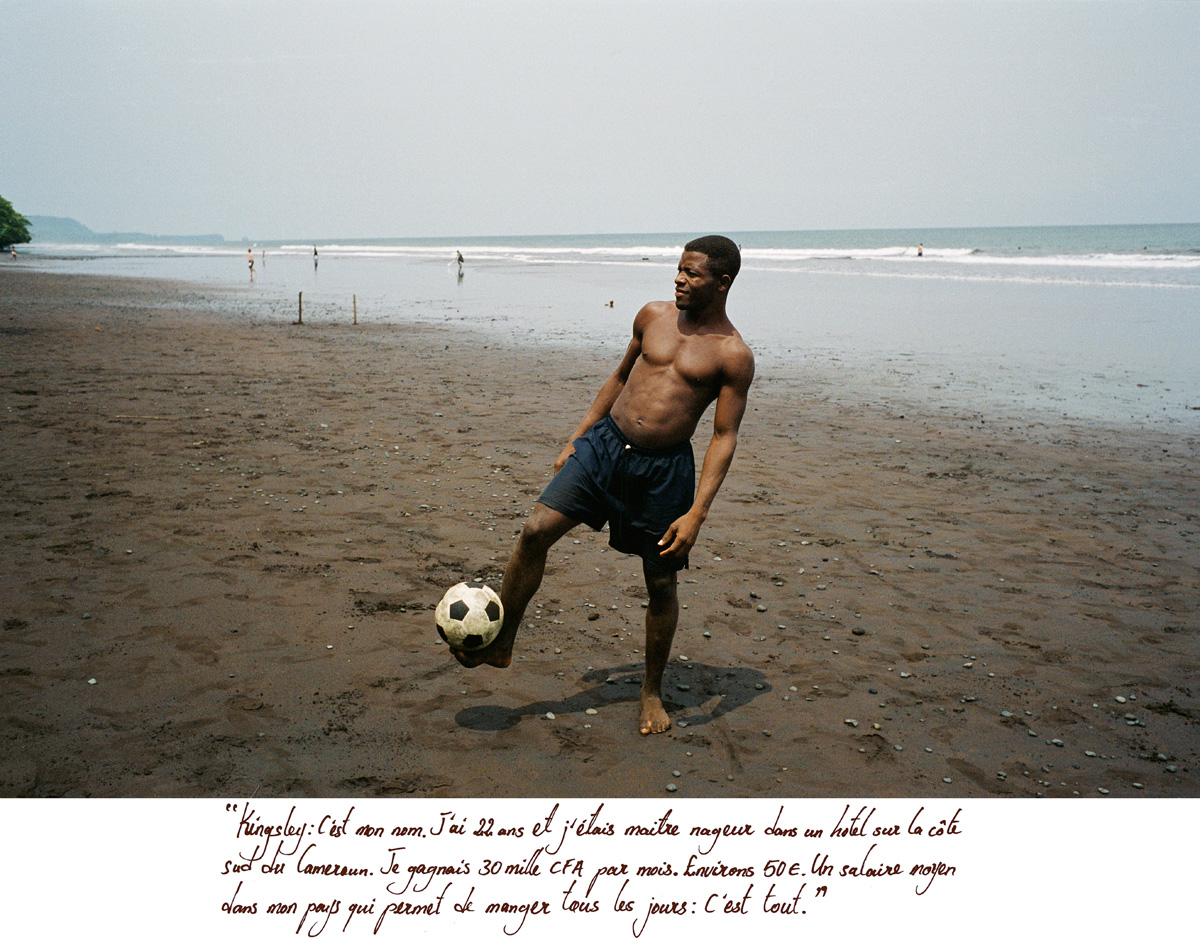

" My name is Kingsley. I'm 22. I was a hotel lifeguard on Cameroon's southern shore. I was earning about 50 € a month. It's an average salary in my country: it allowed me to eat, no more. "

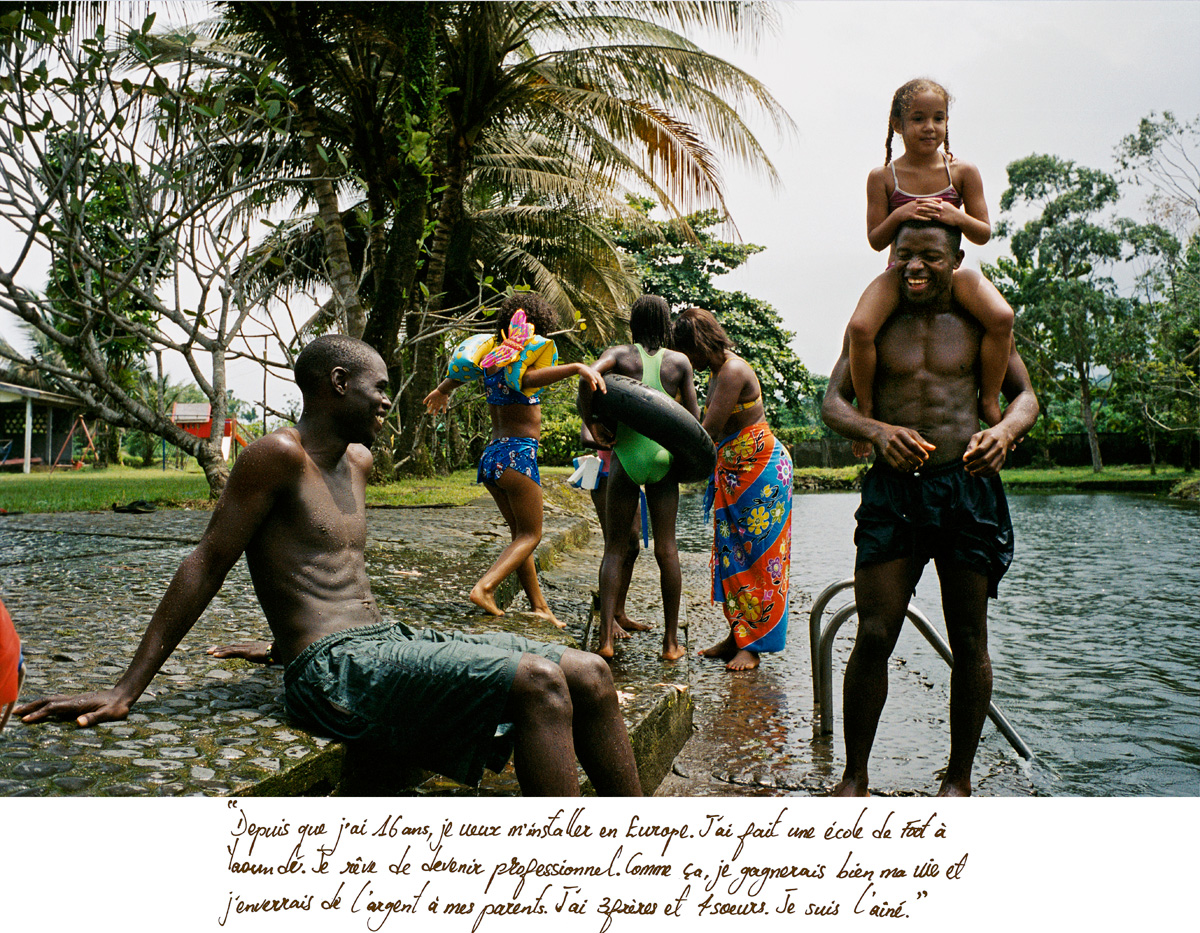

" Since I was 16 years-old, I dreamt of moving to Europe. I entered a soccer school in Yaoundé. My dream was to become a professional soccer player. I wanted to make a living to send money to my parents. I have 3 brothers and 4 sisters. I'm the eldest. "

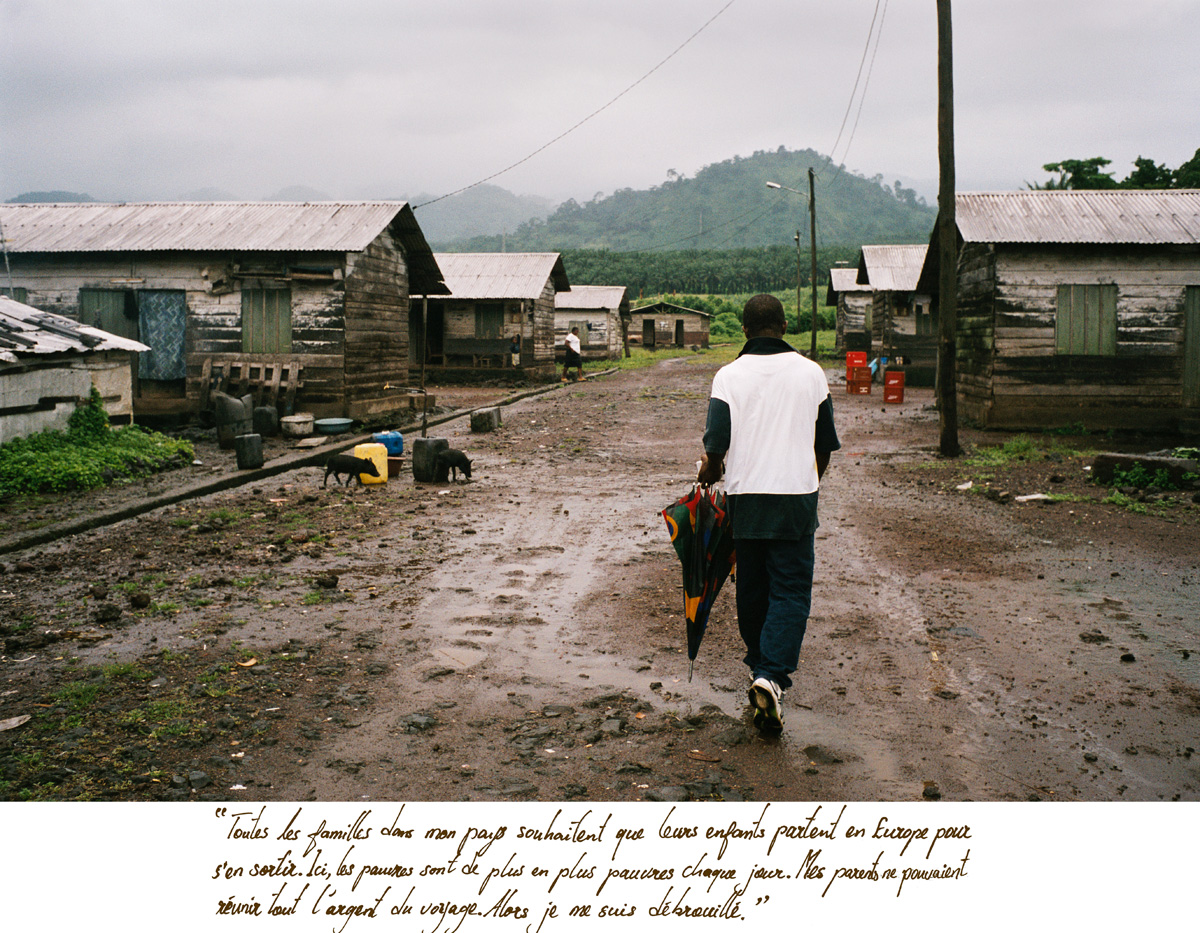

"Every family in my country wishes their children to leave for Europe to make it out. Here, the poor become poorer on a daily basis. Because my parents couldn't find all the money for my trip, I made my way by shifts. "

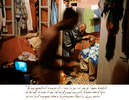

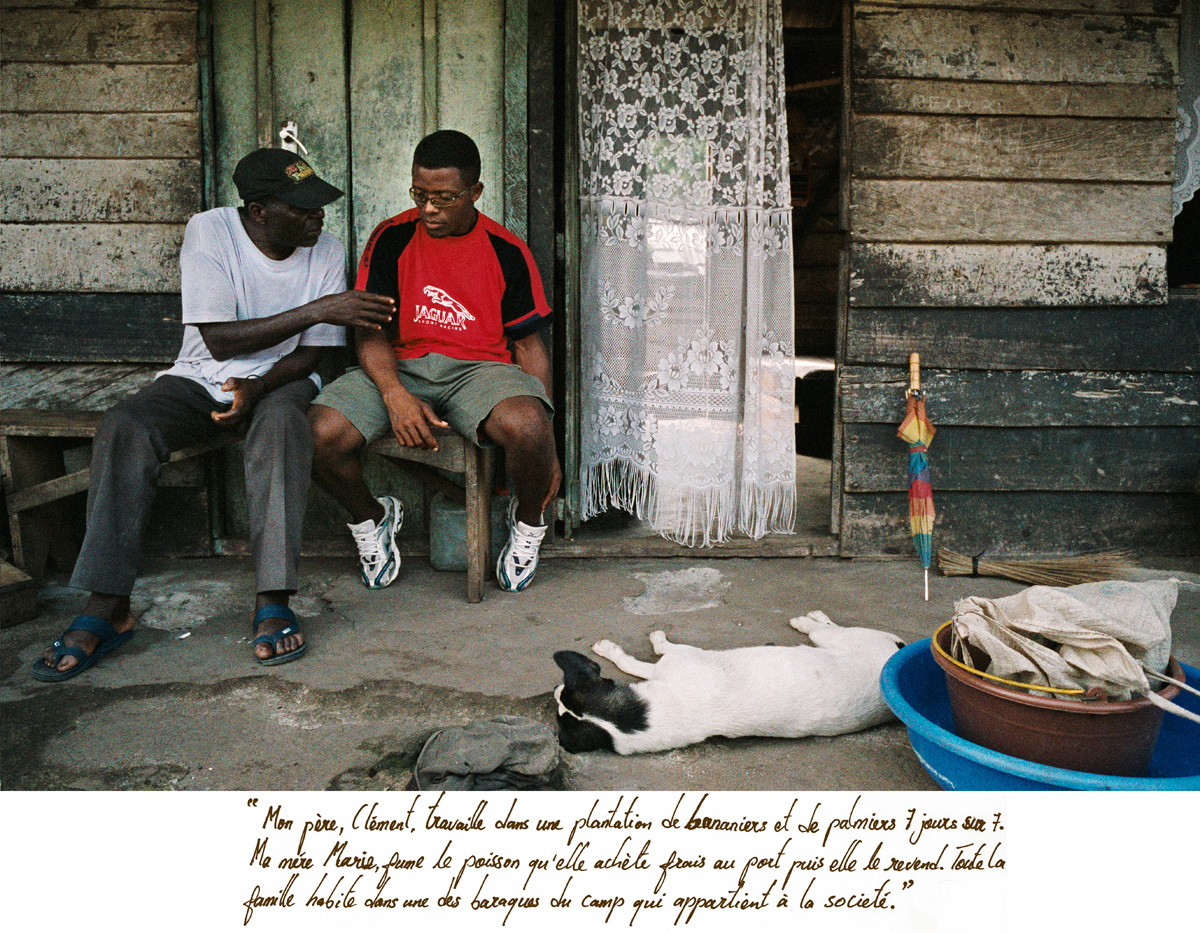

" My father, Clement, works seven days a week in a banana and palm trees plantation. My mothers buys fresh fish at the port, smokes it, and sells it. My whole family is housed in a barrack house owned by the plantation company. "

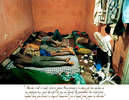

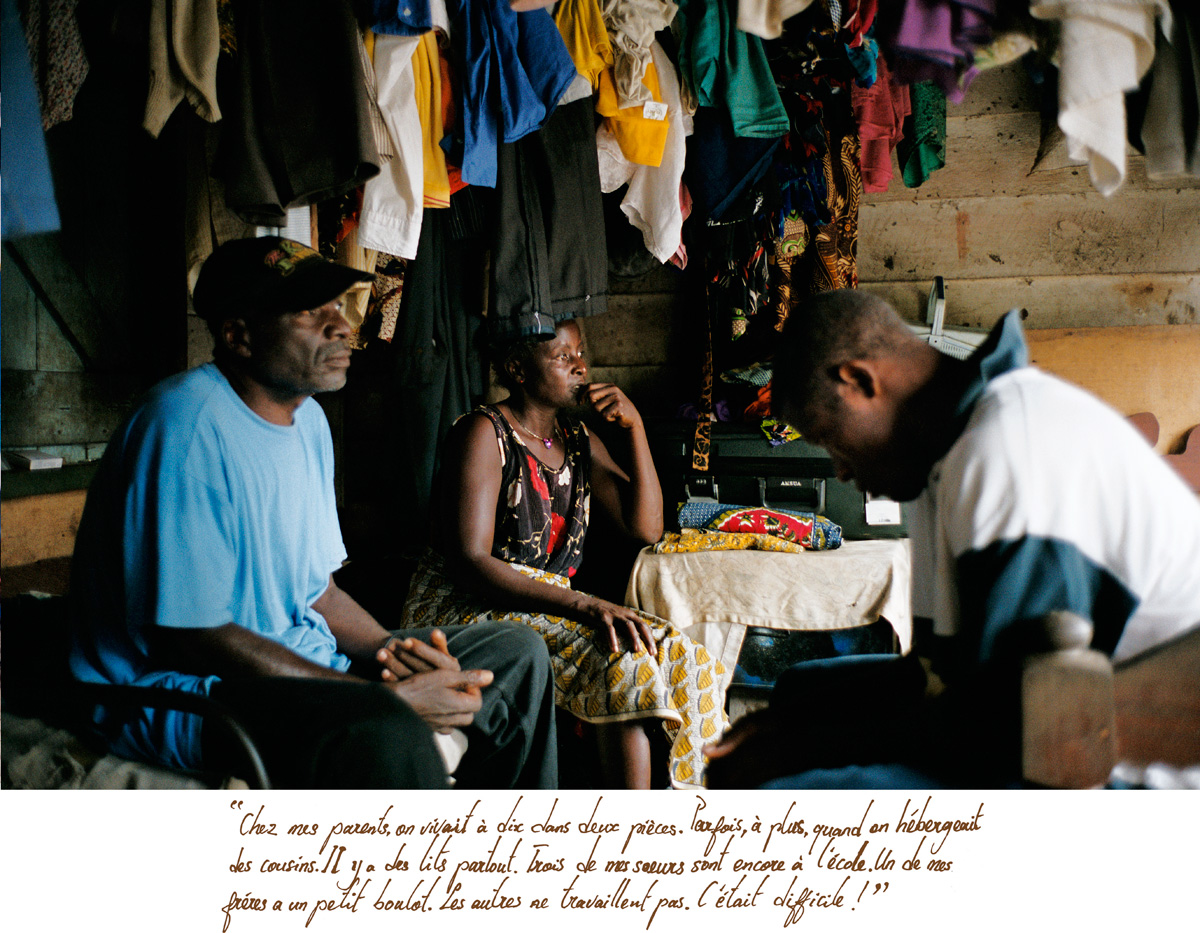

" The ten of us were living in two rooms. Sometimes we even housed cousins as well. Beds are everywhere. Three of my sisters are still studying, and a brother of mine as a low-paid job. No one else worked. It was hard. "

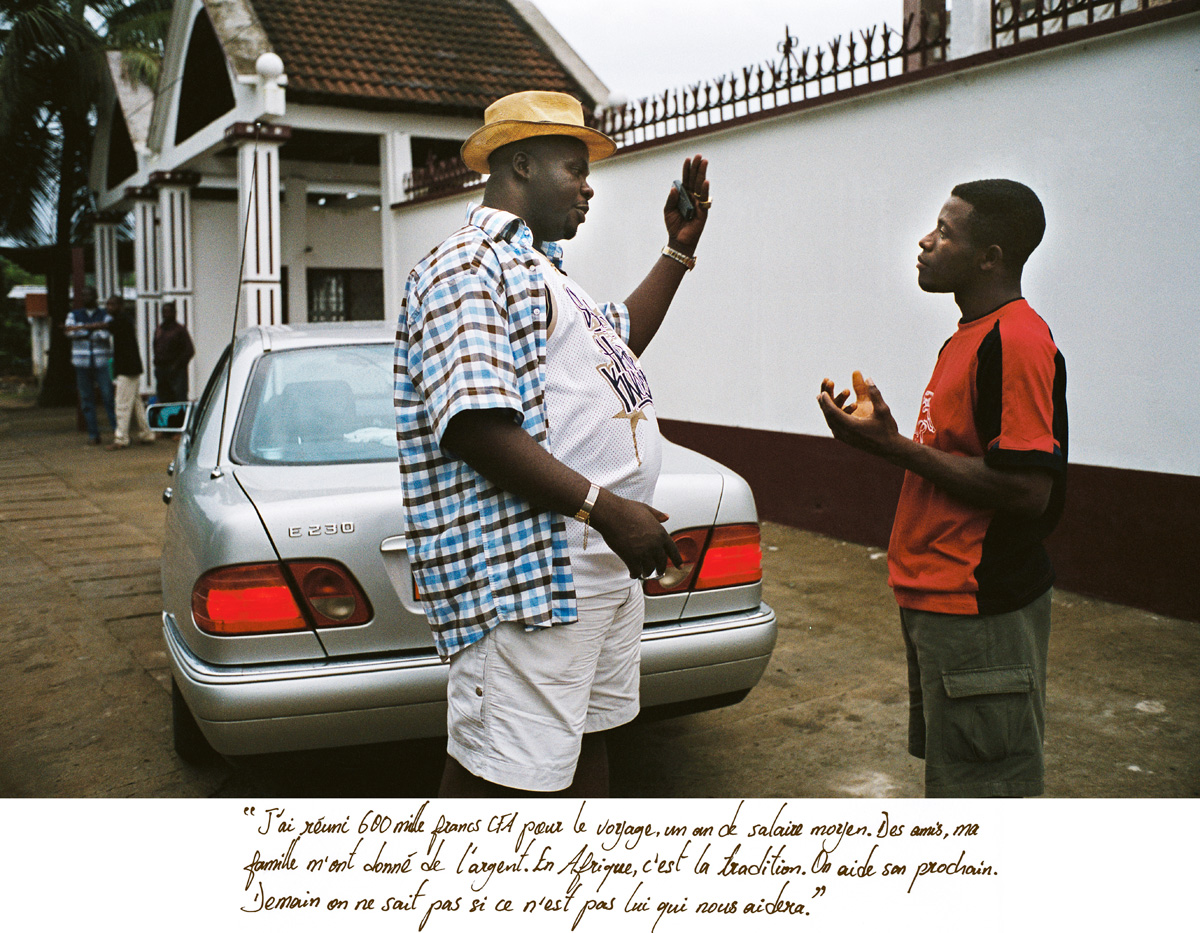

I raised CFA France 600.000, a year of salary. Friends and family lended me money. It's an african tradition. You help someone because you never know if you may need him in the future.

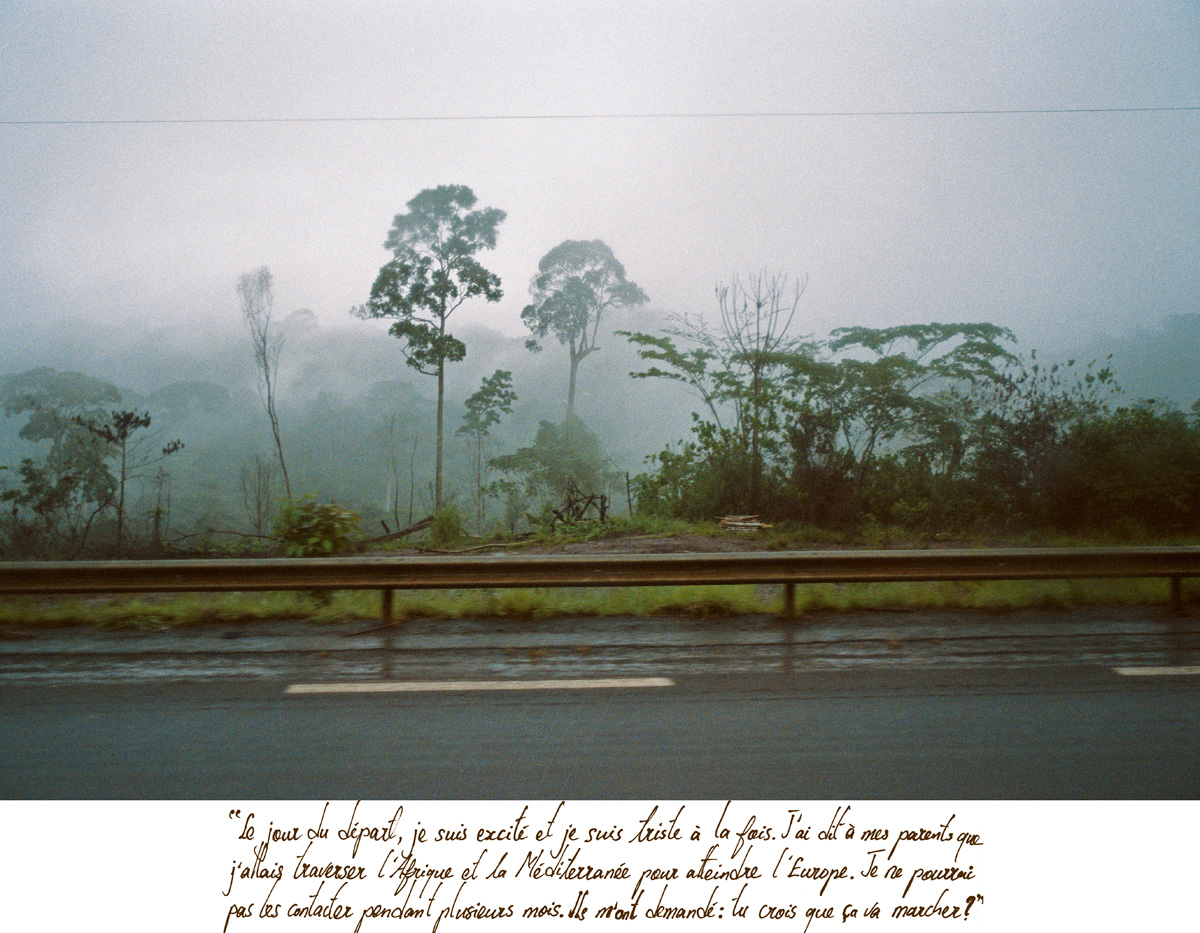

" The day I'm leaving, I am both excited and sad. I've told my parents I will go across Africa and the Mediterranean Sea to reach Europe. I won't be able to talk to them in months. They've just asked: do you think you will make it? "

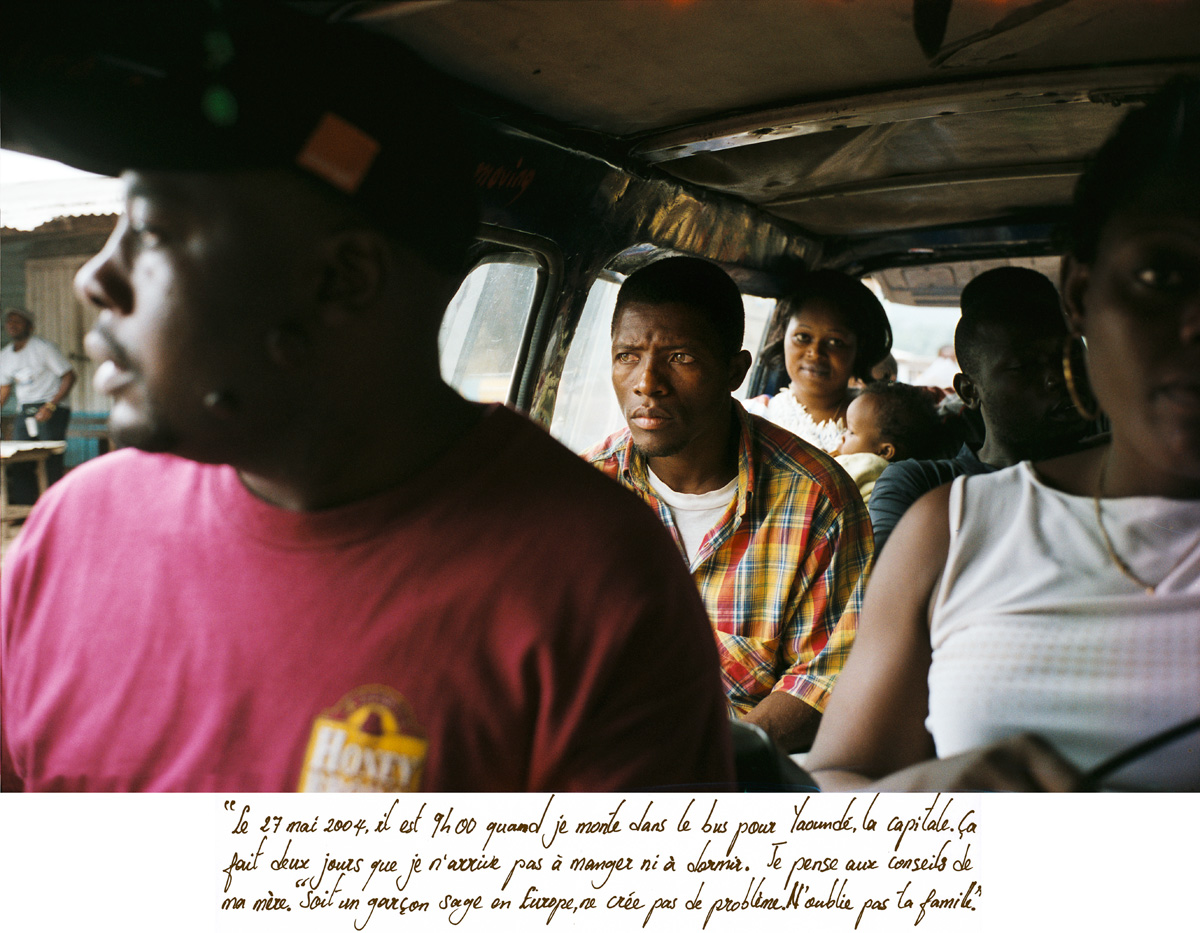

" It's 9 am on the 27th of May 2004 when I board on the bus to Yaoundé, the capitale. I haven't been able to eat or sleep for the past 2 days. I think of my mother's advice: be a good boy in Europe, to get into trouble, don't forget your family. "

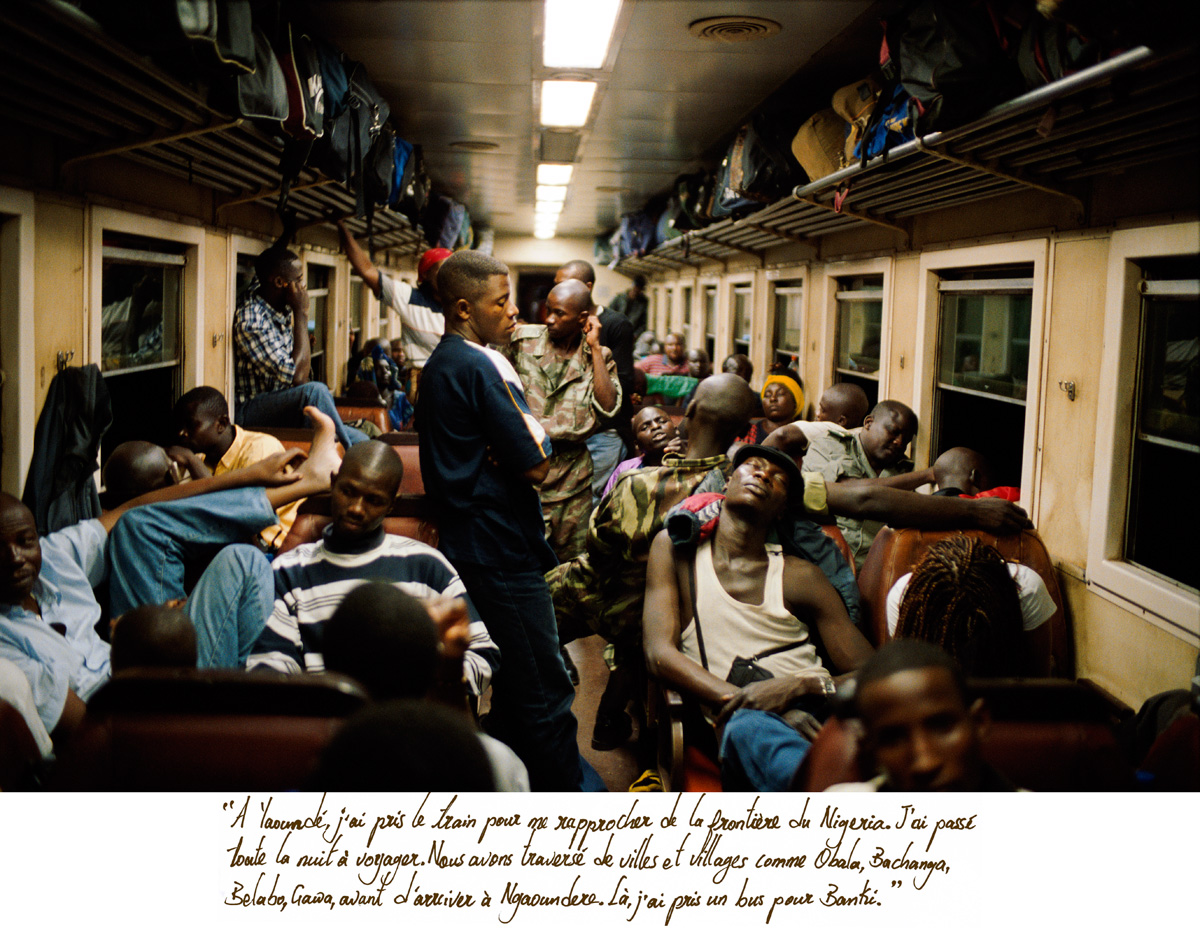

" In Yaoundé, I took a train to get closer to the Nigerian border. I spent the night travelling. we went across villages like Obala, Bachanya, Belabo, Grawa, before reaching Ngoundere. There, I took a bus to Banki. "

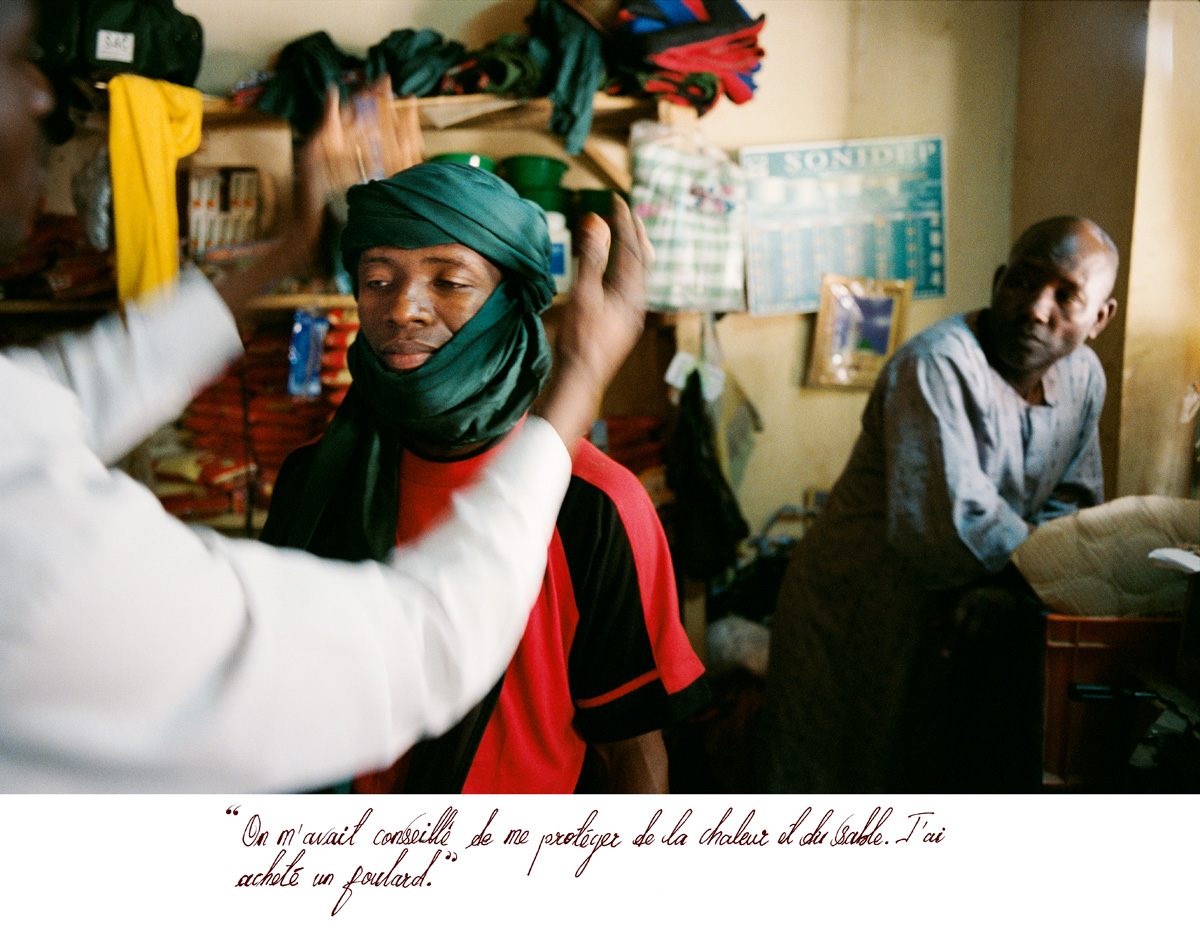

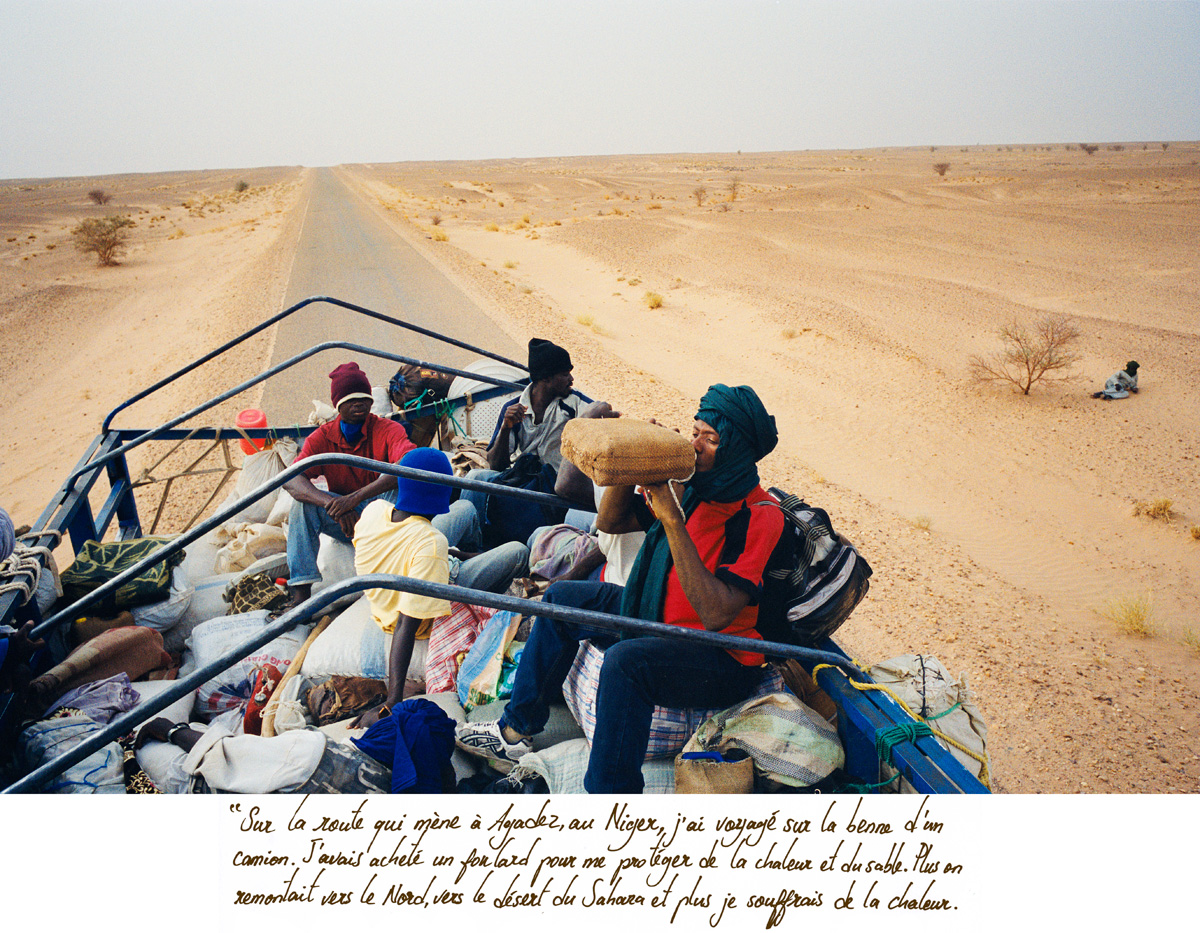

" I was advised to protect myself from heat and send so I bought a scarf. "

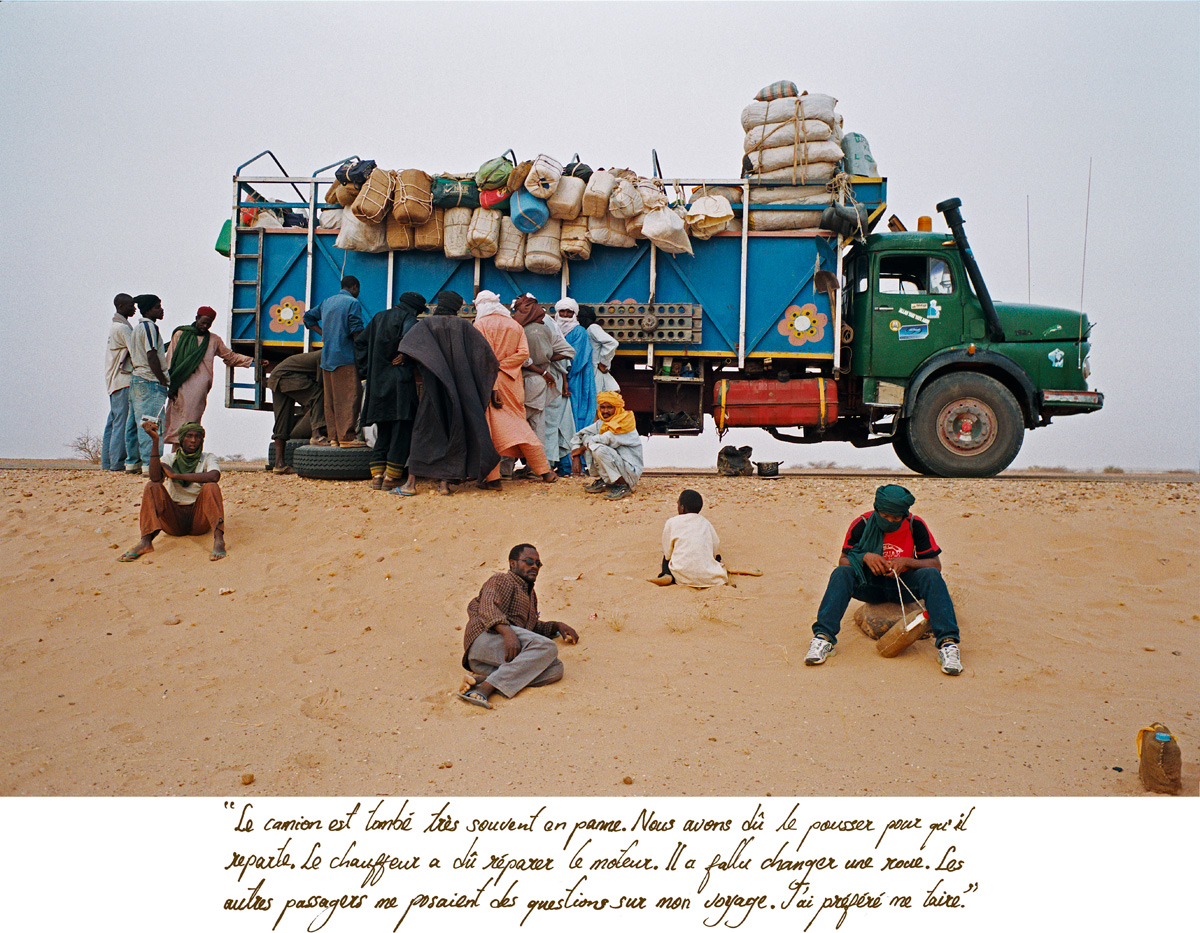

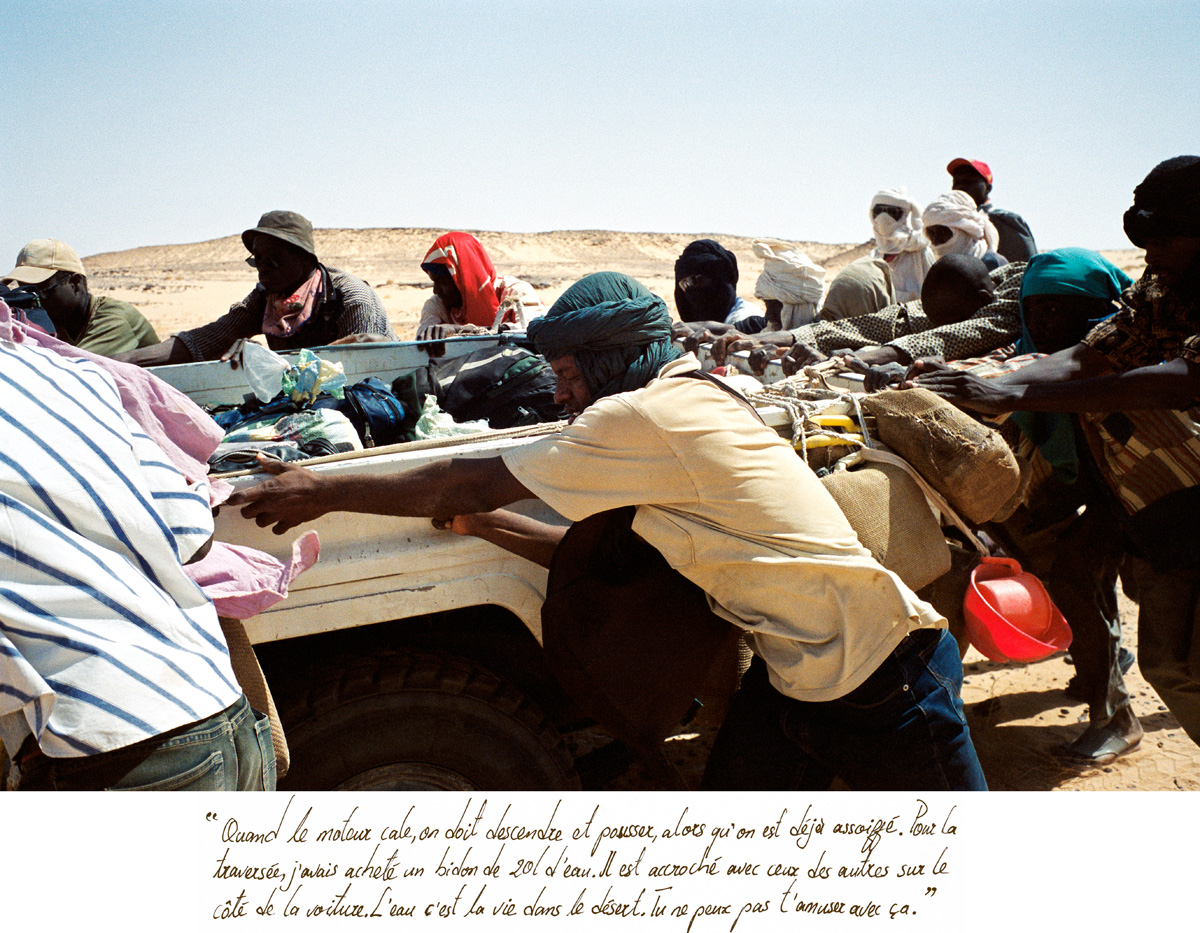

" The truck often broke down. We had to push it so he could start off again. The driver had to repair the engine. He had to change a tire. Other passengers asked me questions about my trip. i decided to stay quiet. "

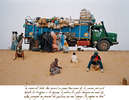

" On the road going to Agadez, Niger, I traveled on a dumper truck. The further we went North to the Sahara Desert, the more I suffered from heat. "

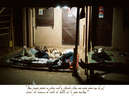

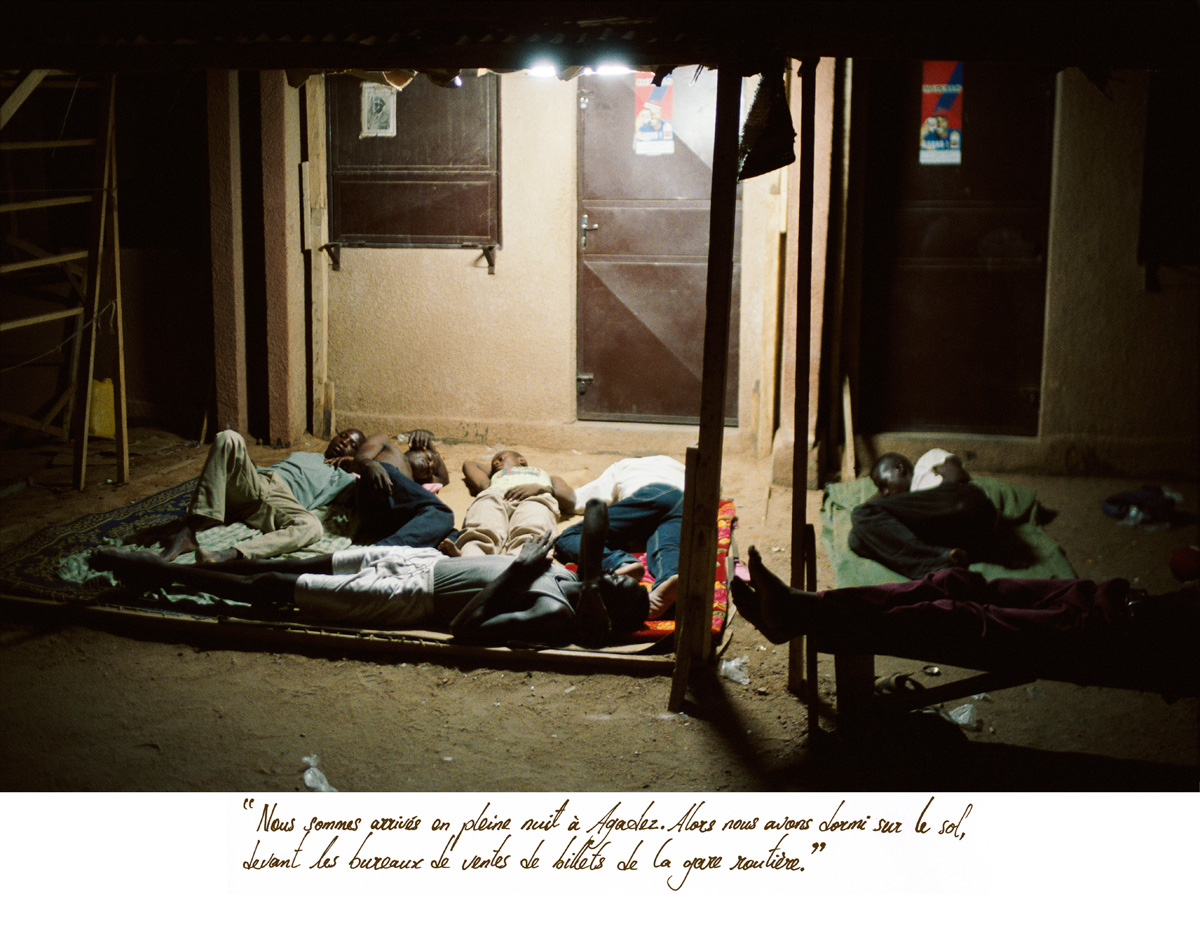

" We reached Agadez in the dark of night. So we slept on the ground, in front of the bus station ticket sale office. "

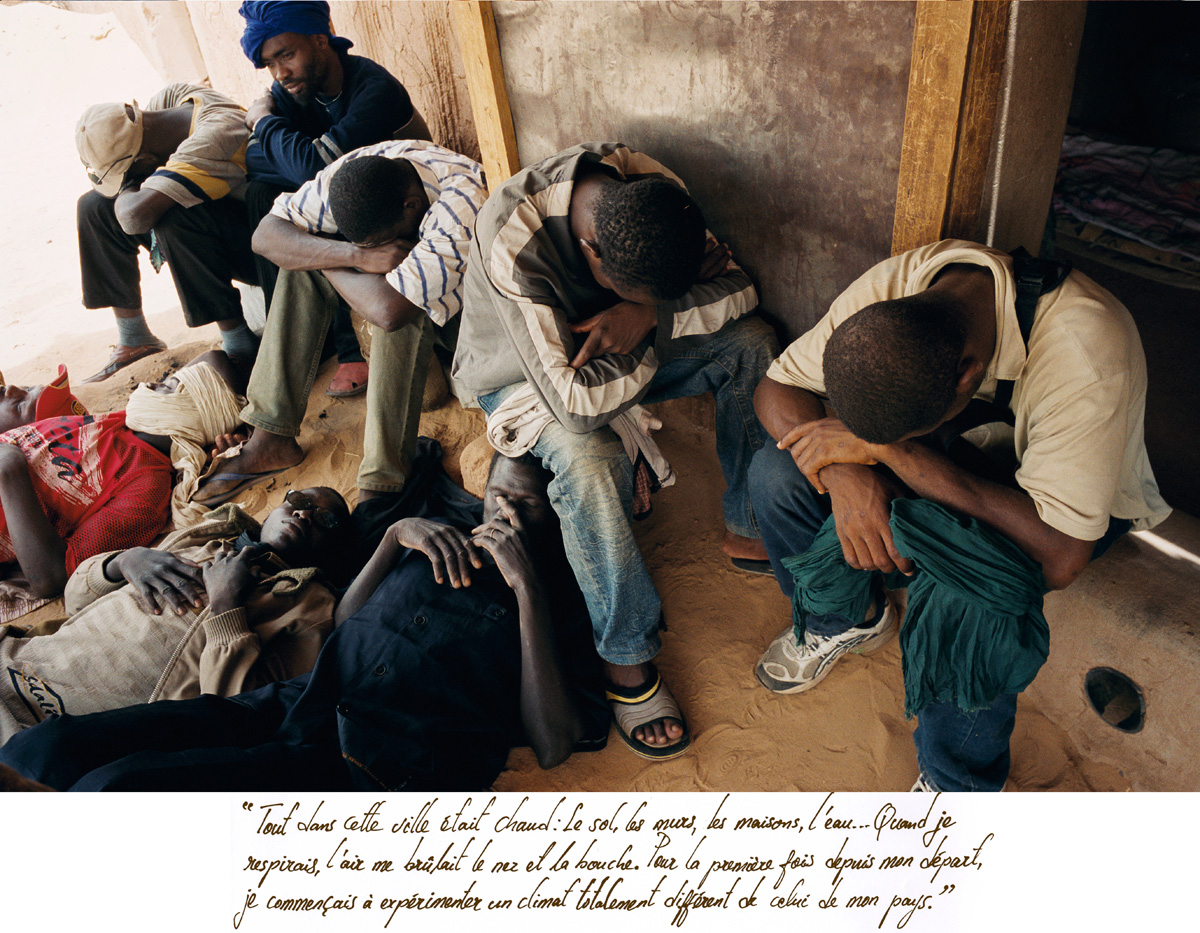

" Everything was hot in the city. The soil, the walls, the houses, the water… When I breath, the air was burning my lips and nose. For the first time since my departure, I experienced a different climate from my country's. "

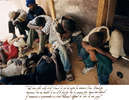

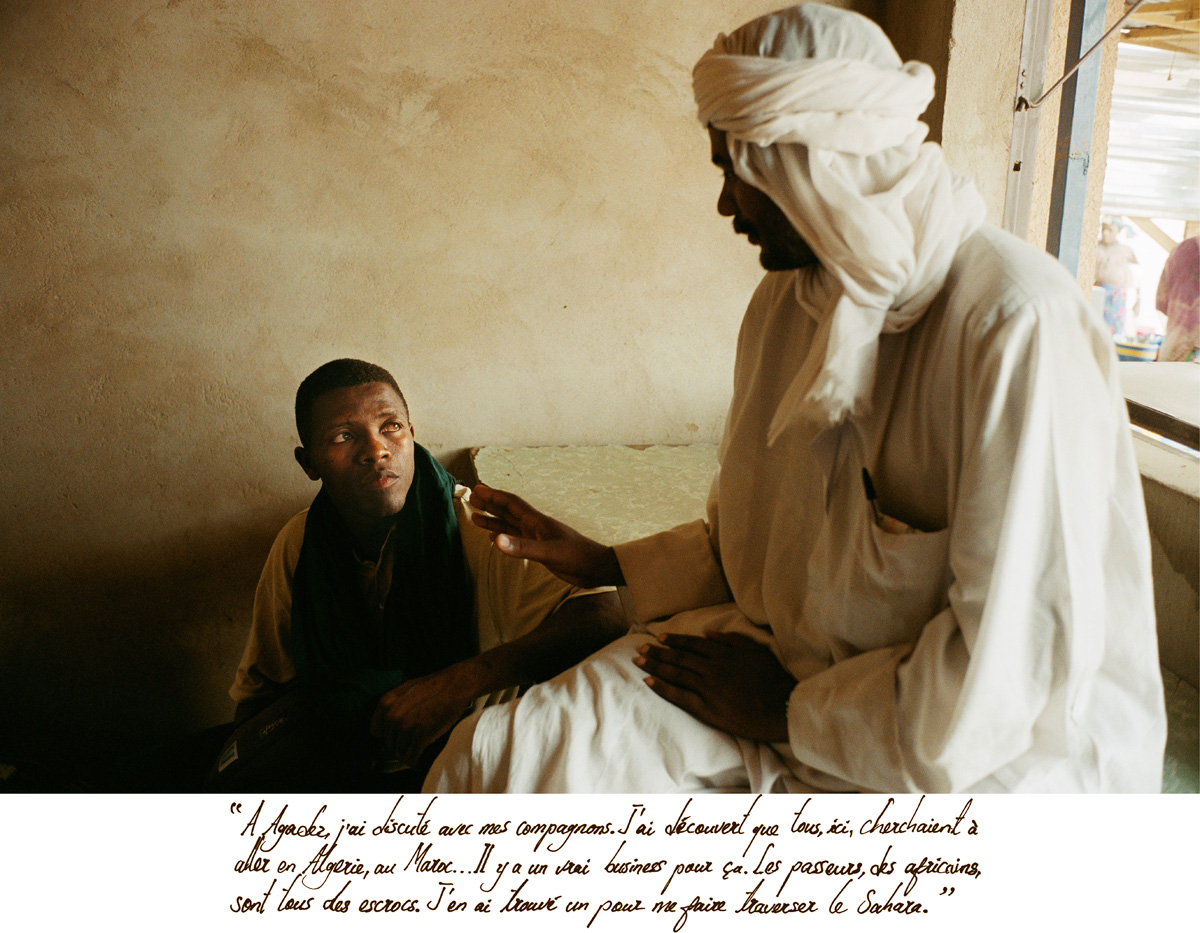

In Agadez, I talked to my companions. I realised they were all trying to go to Algeria and Morocco. There is a real business for this. The smugglers, the Africans, are all crooks. I found one who could take me across Sahara. "

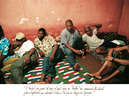

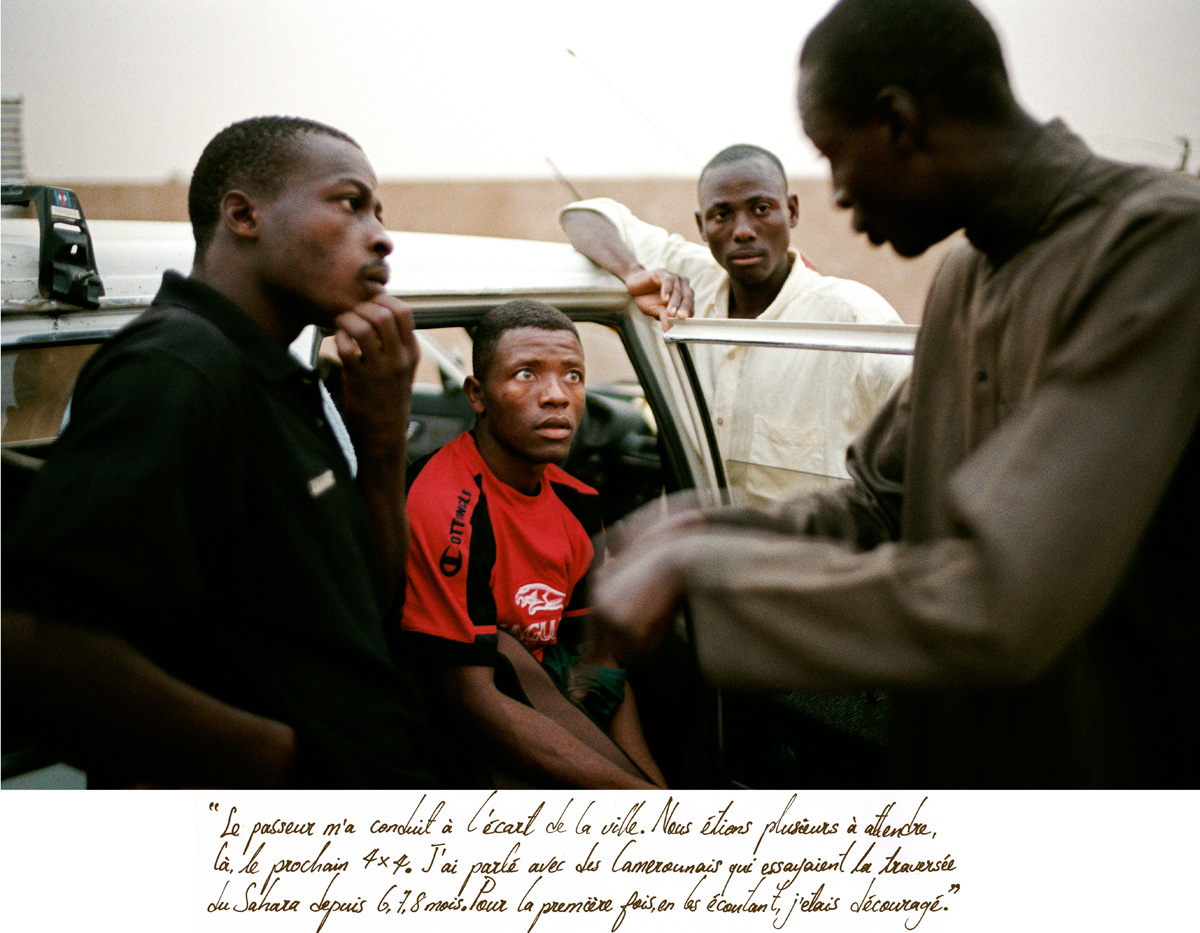

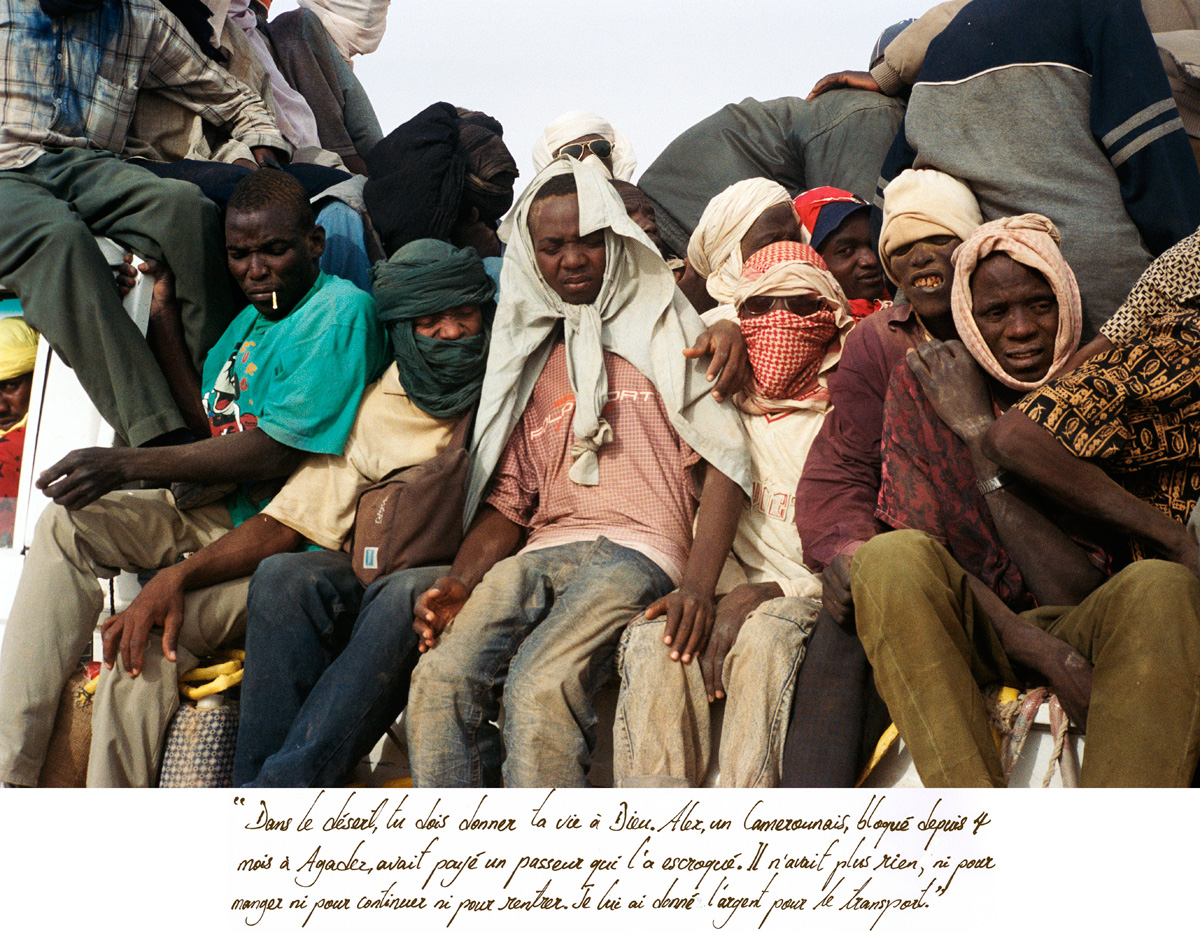

" The smuggler took me outside of the city. several one of us were waiting there for the four-wheels drive. I talked to other men from Cameroon who had been trying to go across for 6 or 7 months. The first time I heard these stories, I felt downhearted. "

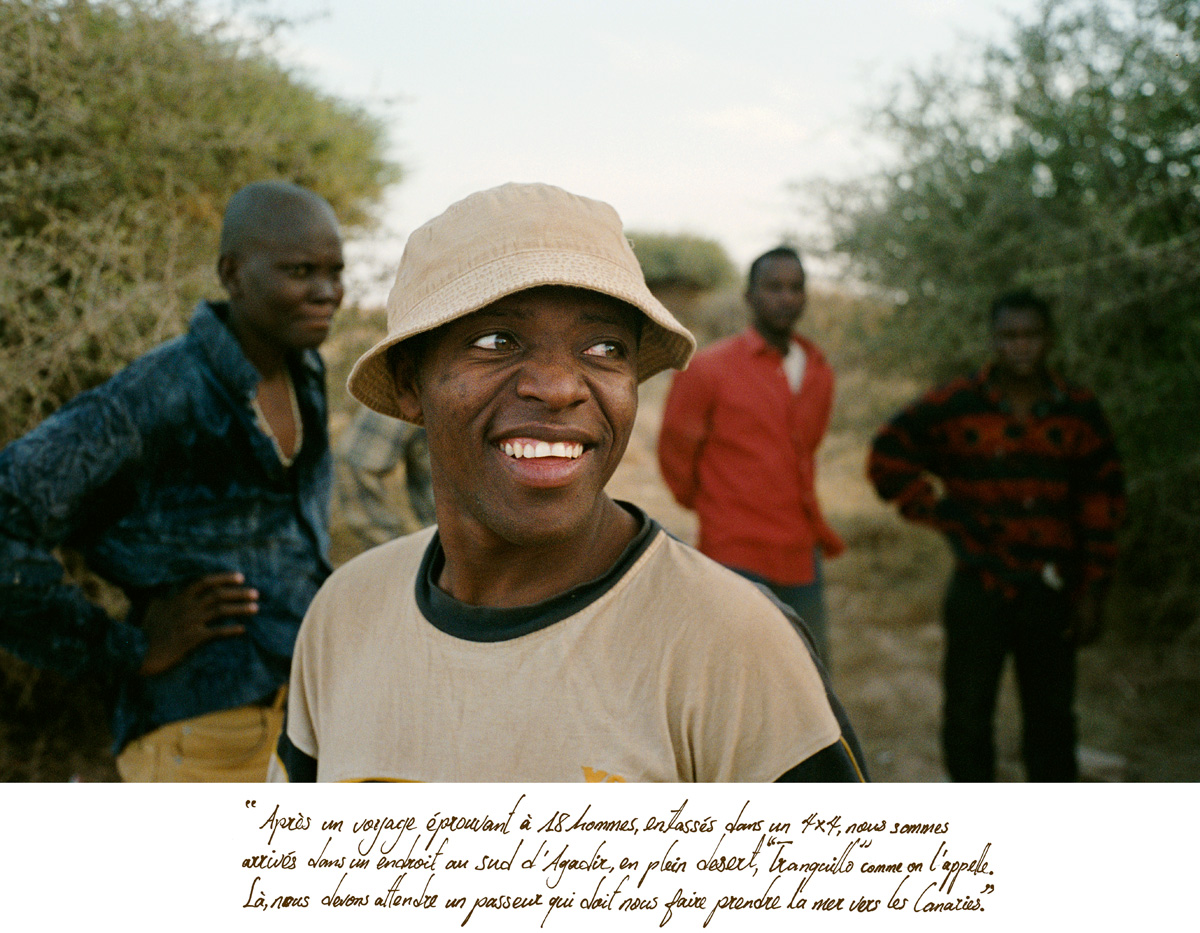

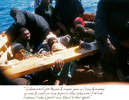

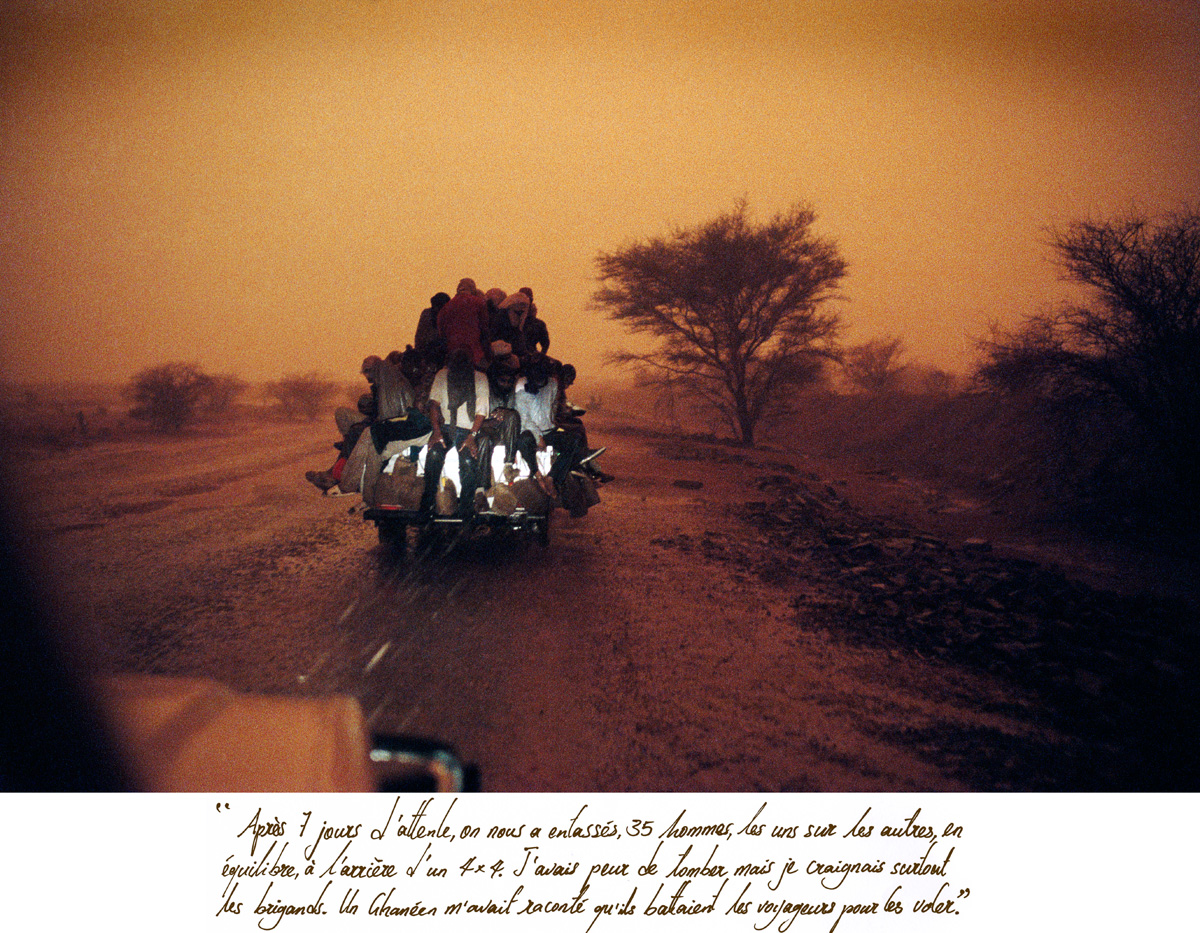

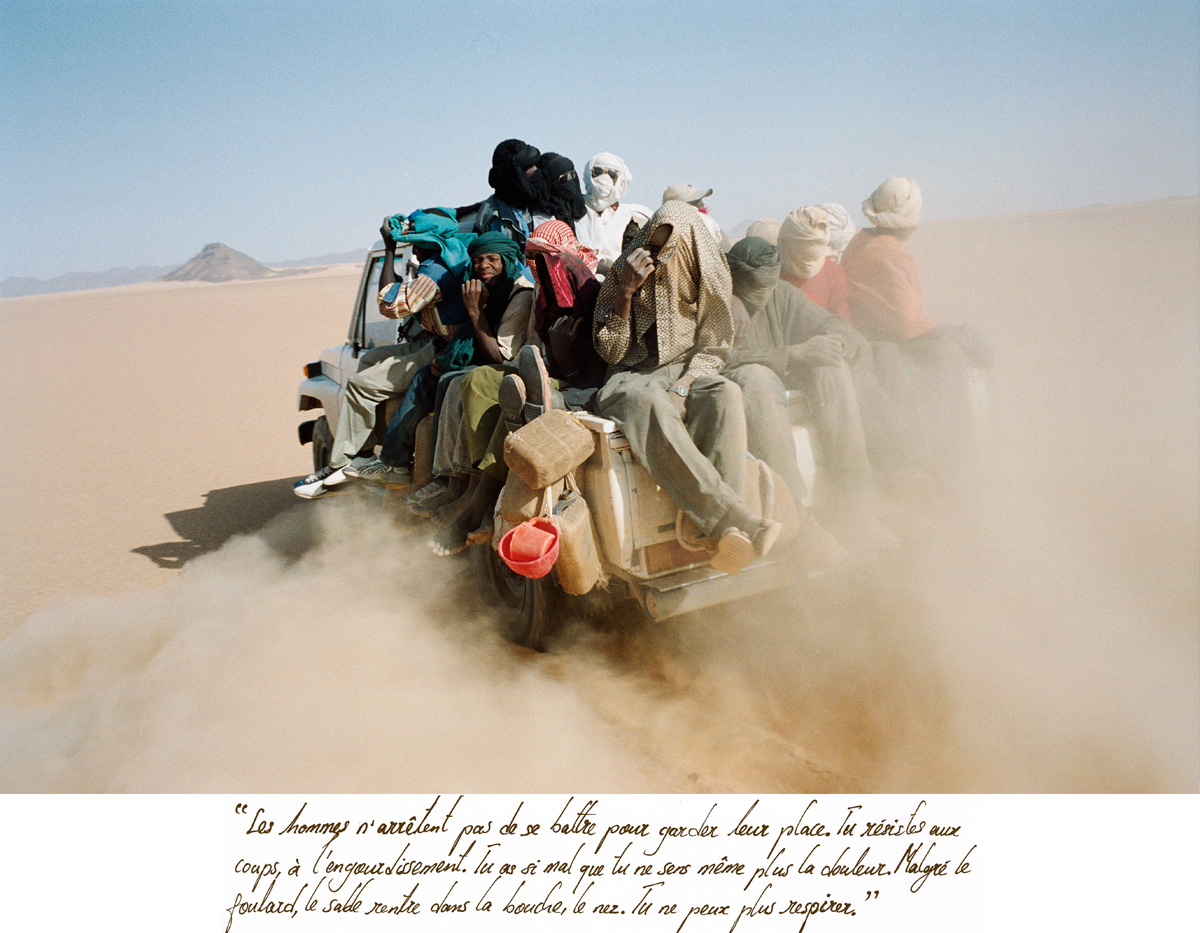

" After seven days waiting, we were packed, the 35 of us, on each other, in balance, on a 4-wheels drive. I was afraid to fall. I feared the thieves the most. A Ganean man told me they beat up the travellers to rob them. "

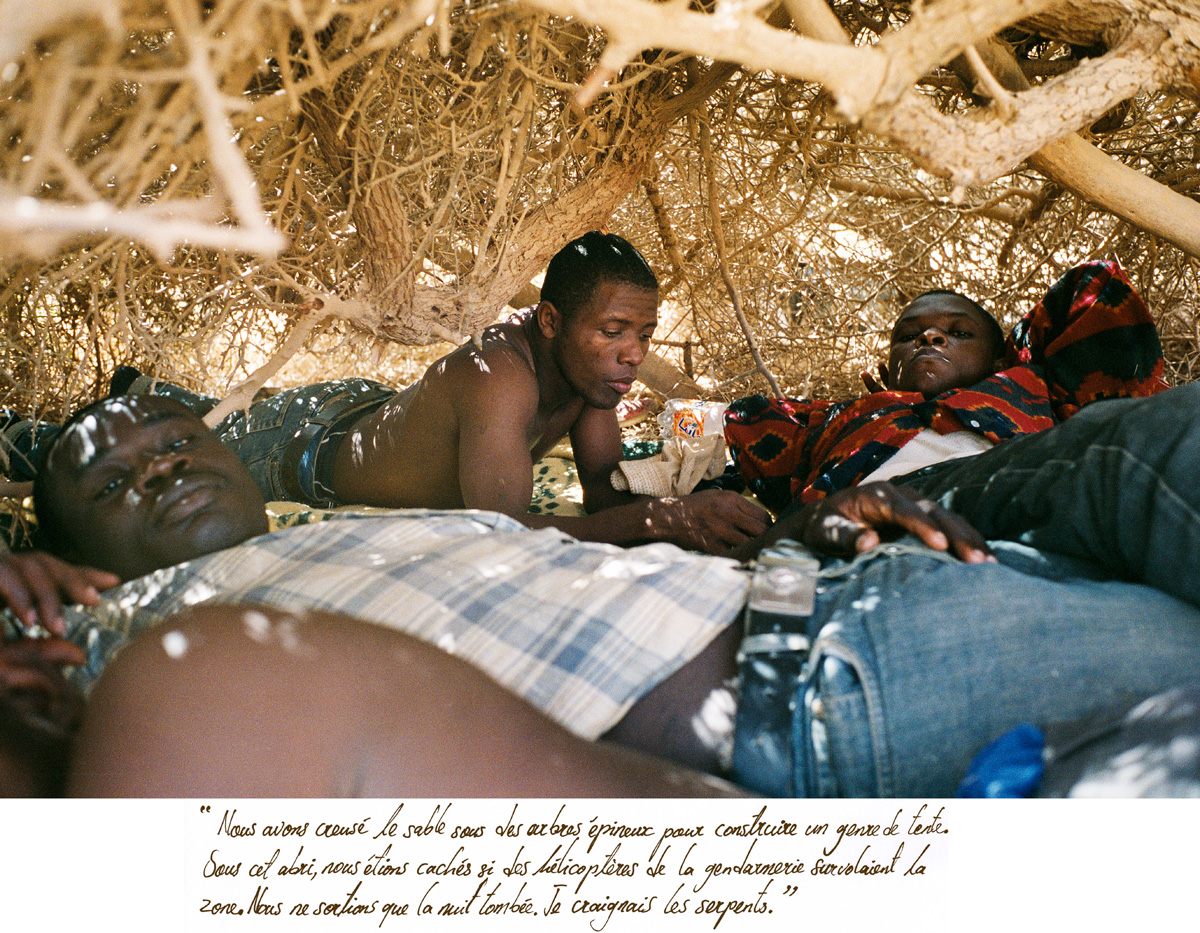

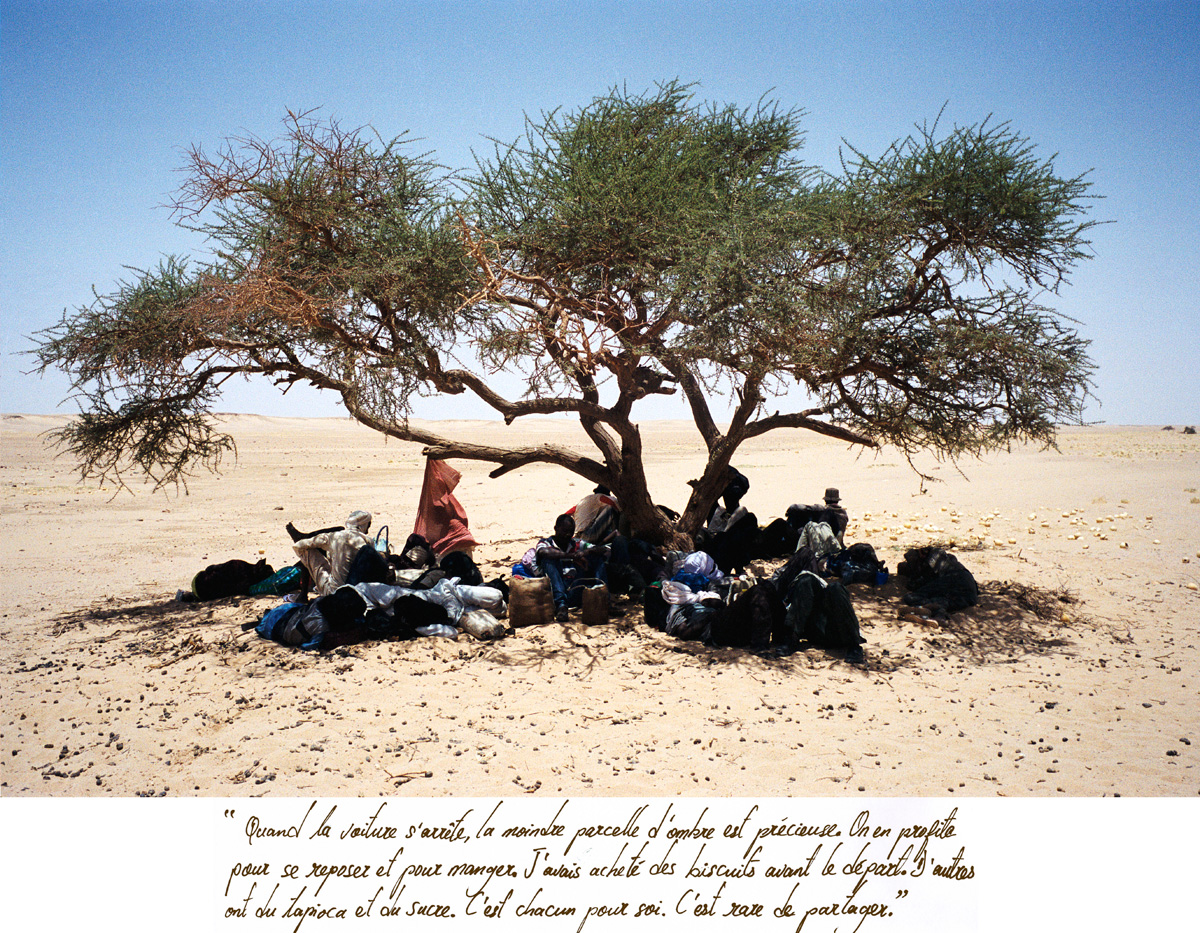

" When the car stops, any shadow is precious. We take the tame to eat and rest. I had bought biscuits before leaving. Others have tapioca ore sugar. It was each for himself, we weren't sharing. "

" The men can't stop fighting for their seat. You have to bear the strikes, and the numbness. The pain is so strong that you don't feel the heat any longer. Even with a scarf, the send enters the mouth and the nose. You can't breath anymore. "

" In the desert, your life belongs to God. Alex, a Cameroonian stuck in Agadez for 4 months, had paid a smuggler who had cheated him. He had nothing left. He couldn't eat, couldn't go further, couldn't come back. I gave him money for the travel. "

" When the engine breaks down, we have to get down and push, even though we are thirsty. For the travel, I had bought a 20 liter water can. It is attached to the others on the side of the car. In the desert, water is life, you can't play with this. "

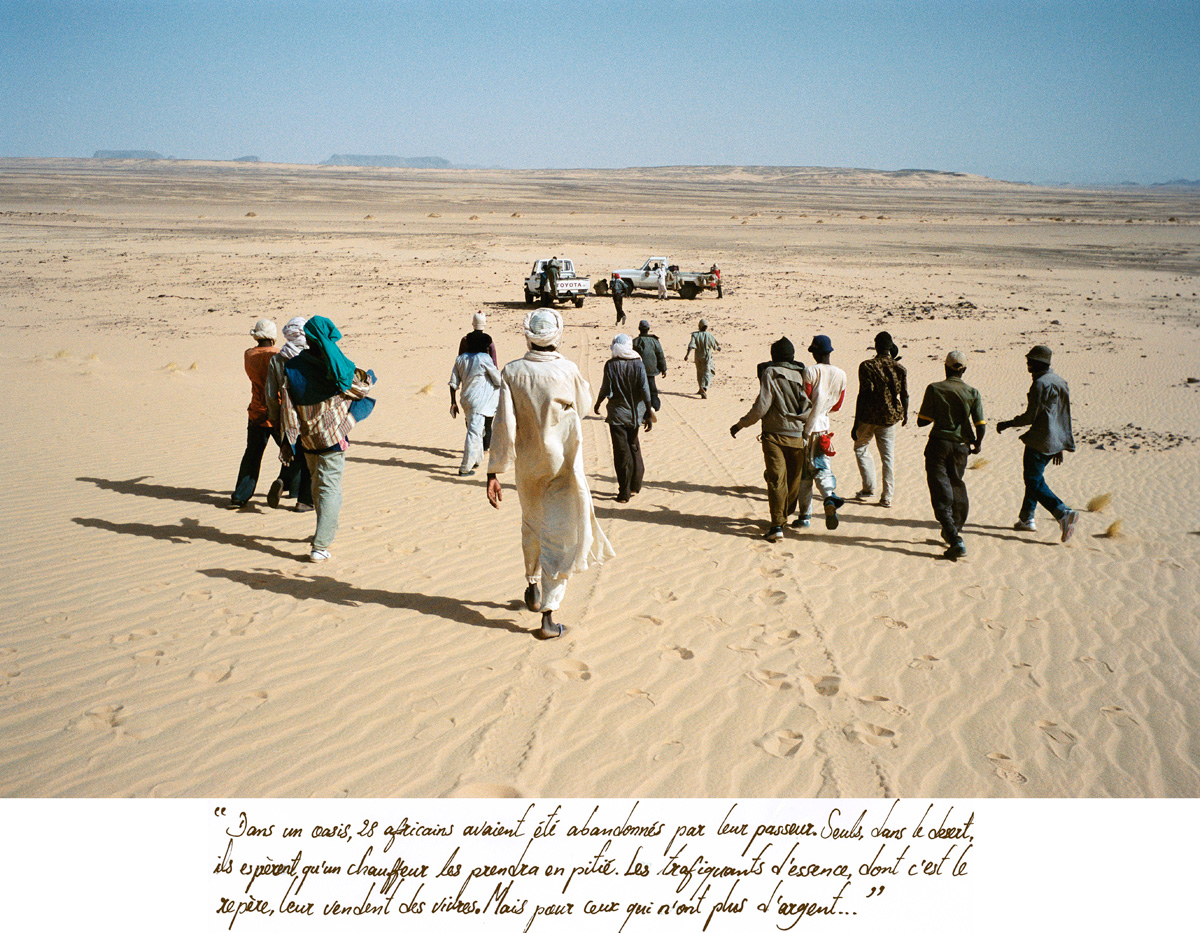

" In an oasis, 23 Africans were abandoned by their smugglers. Alone in the desert, they are hoping a driver will have pity for them. The oil traffickers are selling them goods. But some of the travellers have no money left… "

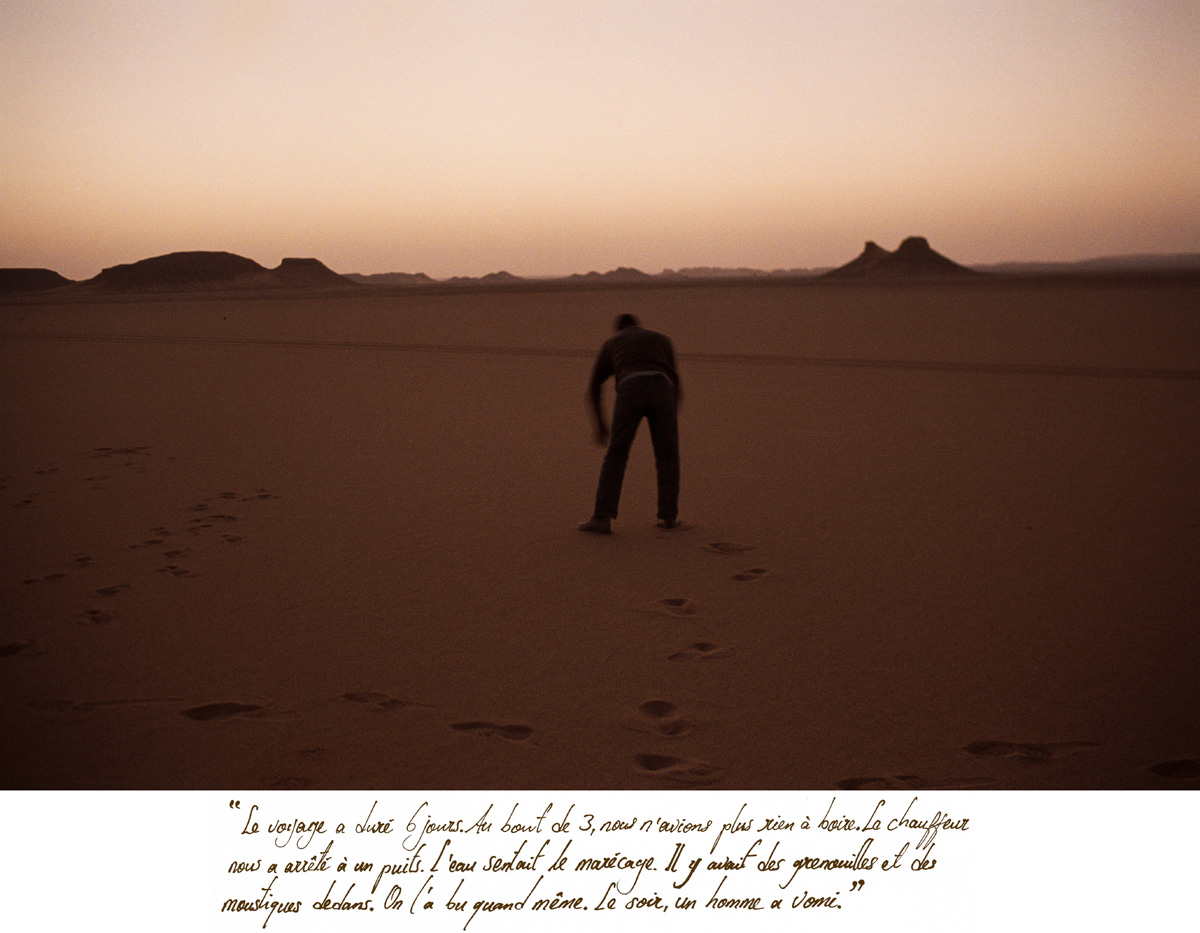

" The trip lasted for six days. After three days, we ran out of water. The driver stopped at a well. The water smelled of swamp. There were frogs and mosquitos. We had to drink it. At night, a man threw up. "

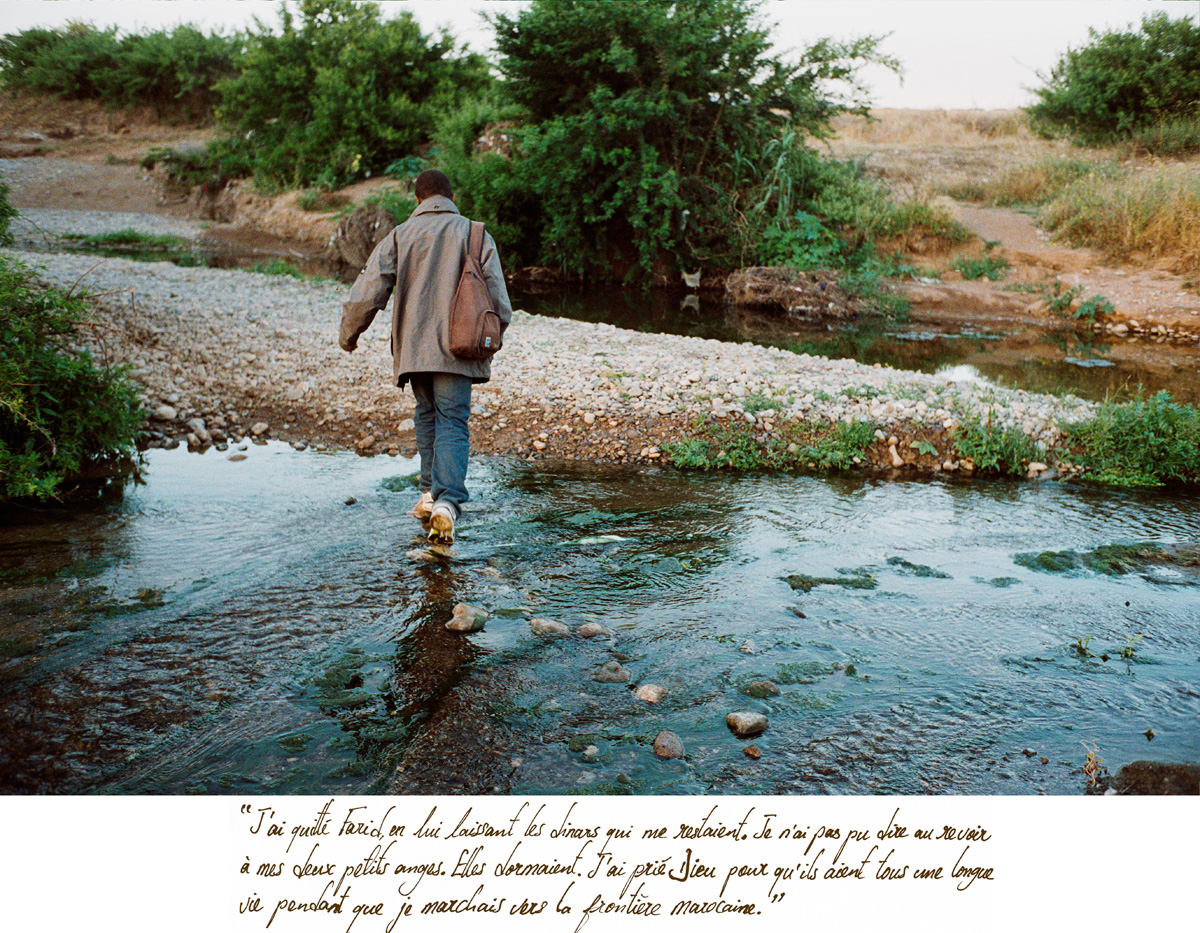

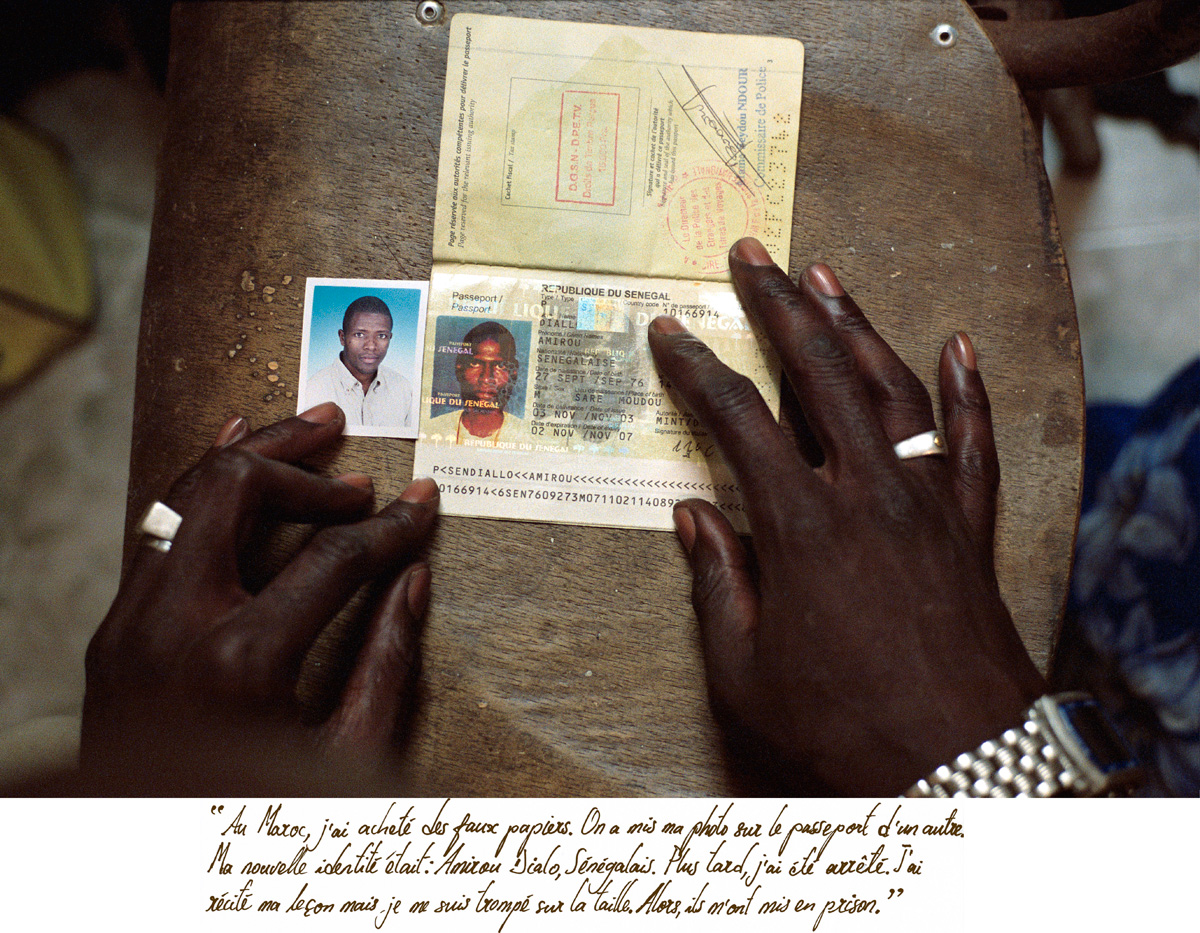

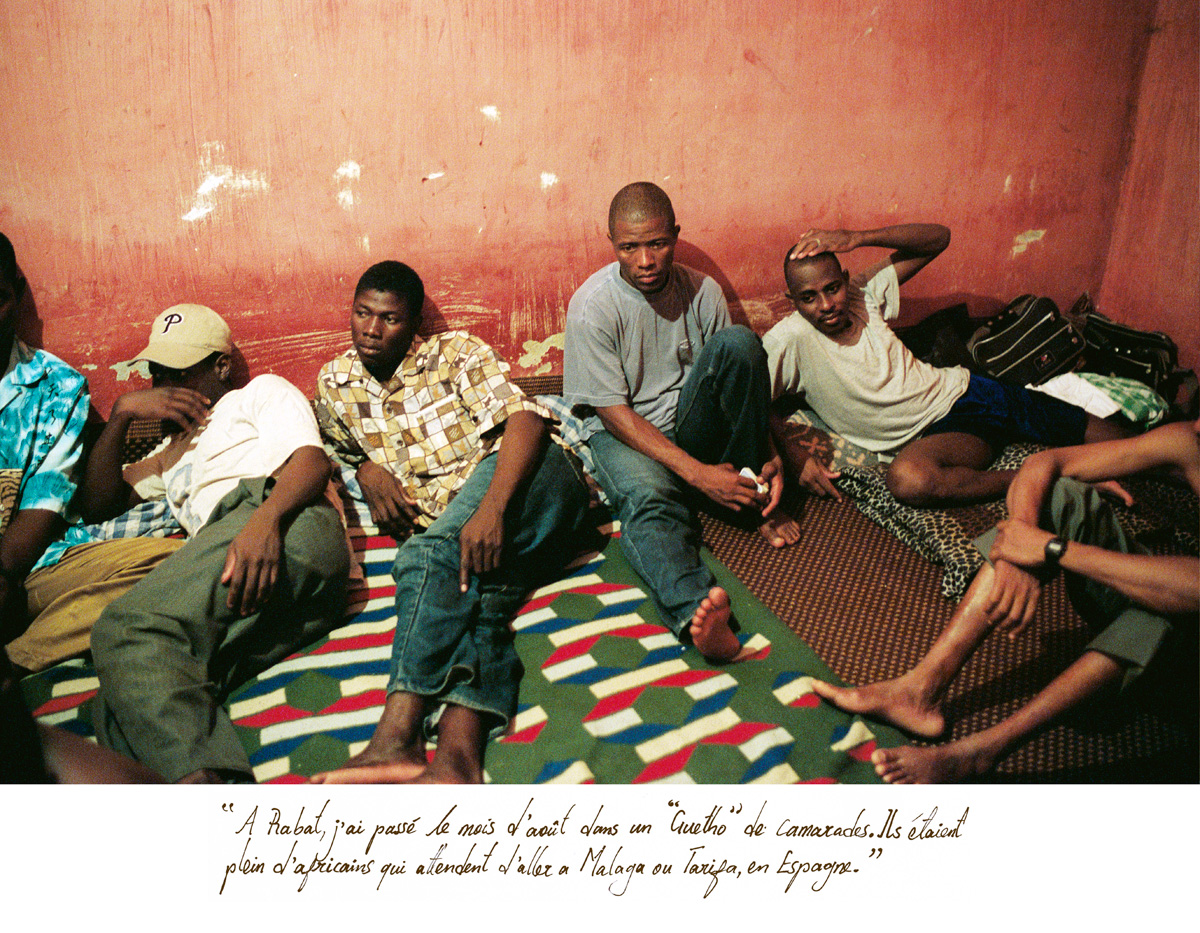

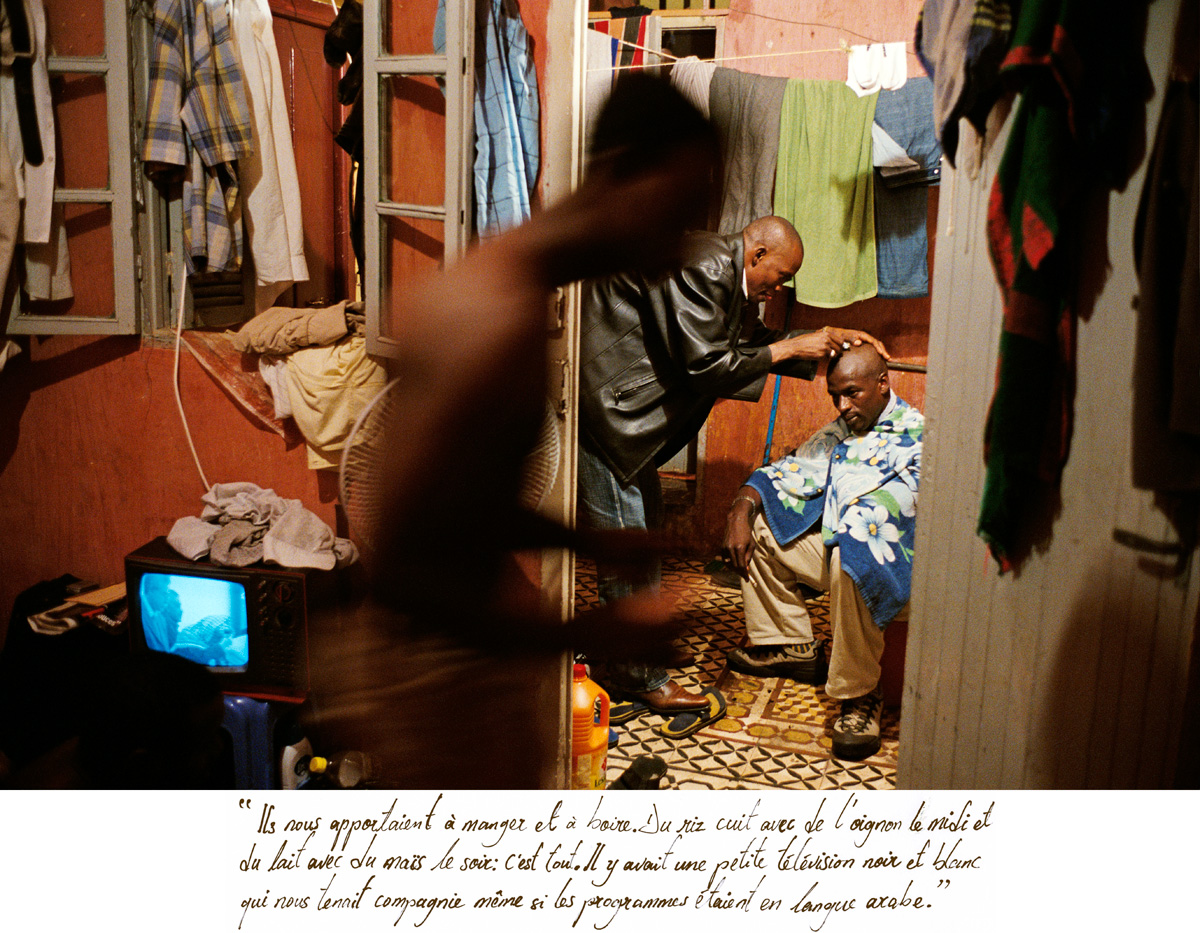

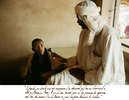

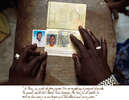

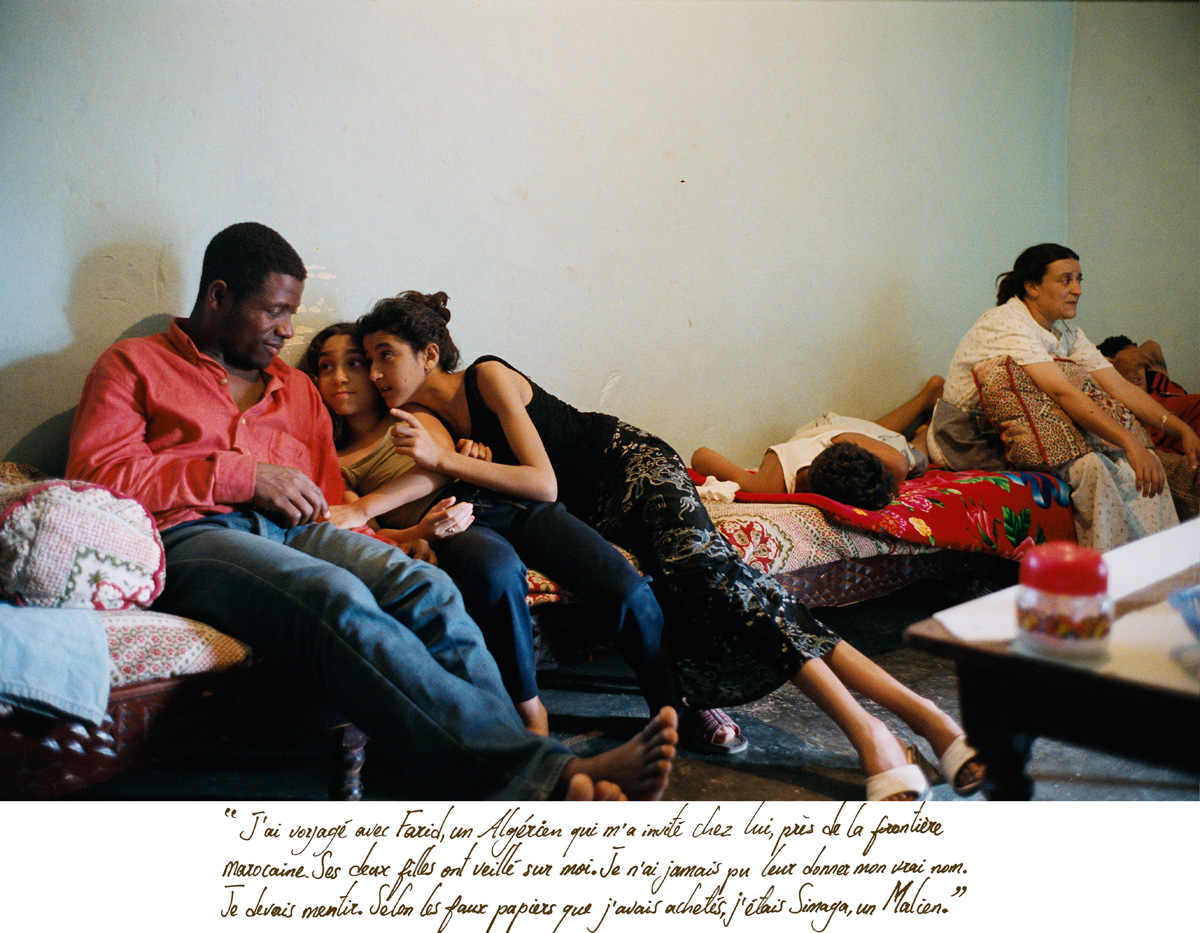

" I travelled with Farad, an Algerian man who invited me in his home, near the Maroccan border. His two daughters took care of me. I could never tell them my real name. I had to lie. According to the fake IDs I had bought, I was from Mali, and called Simaya. "